WKU’s Special Collections Library holds the records of many local women’s clubs in its Manuscripts & Folklife Archives: the Current Events Club, the Browning Club, the Twentieth Century Club, the LARTHS Literary Club, the Mothers Club, the Pierian Club, the Delineator Club, the Eclectic Book Club, the Severance Club, and the oldest (1880) of Bowling Green’s women’s clubs, the Ladies Literary Club, to name just a few. For the first time, we can now include an African-American women’s club on our list.

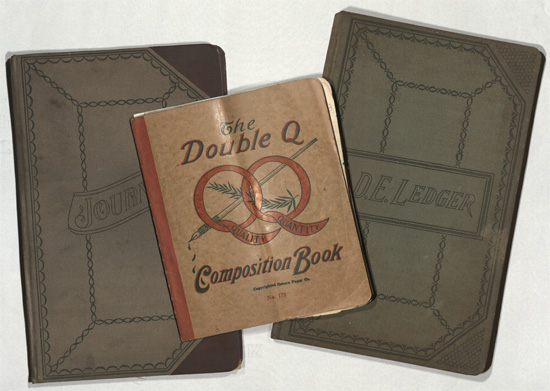

The Ladies Art Club was founded in 1906 by Virginia Mitchell and her minister husband Robert, the president of Simmons Memorial College in Bowling Green. Its first president was M. Celestine Slaughter, a teacher at State Street School, the city’s first school for African Americans. We have yet to learn of the club’s earliest years, but minute books recently recovered from the former Southern Queen Hotel on State Street chronicle its activities during the late 1930s, early 1940s and mid 1950s. The membership roll, which usually listed about a dozen women, included Ashula P. Williams who, along with her aunt Mattie Covington and daughter Dolores (Williams) Moses, operated the Southern Queen as a hotel for African-American travelers.

Like most such organizations, the Ladies Art Club was grounded in faith, fellowship, intellectual enrichment, and philanthropy. Meetings regularly included prayer, scripture readings, song, discussion of current news, a tasty meal, and the collection of funds for various good works: flowers for the sick, Christmas baskets for the aged, shoes for needy children, furniture for the State Street School library, and spending money for Kentucky State University students. Over time, the club contributed from its “sinking fund” to the Kentucky Club Women Scholarship Fund, the March of Dimes, and organizations fighting tuberculosis, cancer and venereal disease.

One of the regular activities of the club was an annual art exhibit. Held at a member’s home and open to the public, the exhibit featured fancy sewing works such as pillowcases, tea and guest towels, and pot holders. Members were urged – sometimes even admonished – to contribute what they could in order to bring a variety of items to the showing. Another disciplinary measure appeared in the minutes for January 3, 1941, when members were reminded of a club rule “pertaining to gossip”: anyone who did so or caused “discord in any way” would be dropped from the rolls.

In discussions of current news, the club was attentive to matters, both national and local, of interest to the African-American community. When, in September 1953, funeral director James E. Kuykendall and his family were victimized by a cross burning on his property, the club “by common consent” sent a letter to the family deploring the attack on their “peace and happiness.” But other correspondence was more joyful. In 1957, with the club observing its fiftieth anniversary, its first president, M. Celestine Slaughter, wrote from her home in Washington, D.C. in response to a gift. “What great happiness and gratitude overflowed my heart when I opened the package,” she exclaimed, praising the club’s “earnest efforts in bringing needful spiritual and happy relationships to the less fortunate in relieving them of stress and need.”

Click here to access a finding aid and full-text scans of the minute books for the Ladies Art Club. For other club records (women’s and men’s), search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.