Every special collections library that holds war materials has them: soldiers’ letters vaguely addressed from “somewhere in France” or “somewhere in the Pacific.” They might also show more revealing words or lines deftly excised with a sharp blade, and their envelopes may bear a stamp indicating that the contents have been inspected prior to delivery to waiting parents, wives or sweethearts. The reason, of course, was that the letters were censored to keep potentially valuable intelligence from falling into the hands of the enemy.

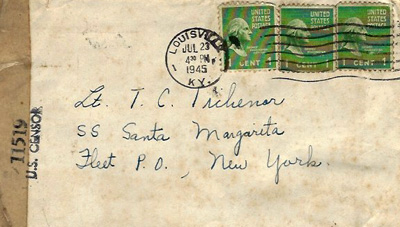

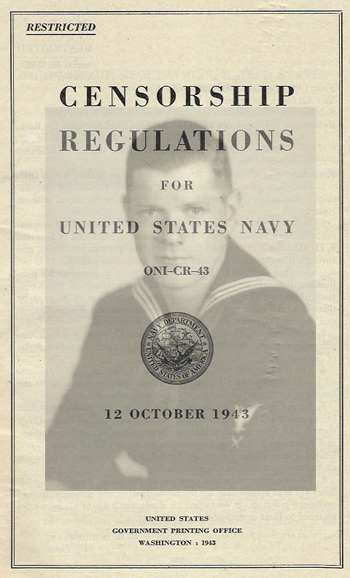

During World War II, the task of censor fell to Calhoun, Kentucky’s Thomas Tichenor after he entered the Navy and received his officer’s commission in 1942. As a convoy communications officer, he was handed the censor’s stamp and a lengthy booklet of regulations governing both outgoing and incoming military mail.

Under the regulations, Navy personnel were permitted to send mail in six ways: by letter; “urgent letter” (an expedited communication arising out of an emergency); V-mail (short for “Victory mail,” in which specially designed letter sheets were microfilmed to save space and the reduced images printed out and delivered to the recipient); post cards; Navy post cards (with preprinted, pre-authorized text and fill-in-the-blanks options); and Parcel Post. Most of the censorship rules were easily justified: no photographs of a military character; no writing in a foreign language; no details of ship locations or strength of forces, munitions and equipment; no disclosure of casualties ahead of the official publication of same; no detailed meteorological data; and no criticisms of the “morale of the collective or individual armed forces of the United States or her allies.” Other communication restrictions barred the keeping of diaries and the transmittal of personal recordings to or from Navy personnel.

The regulations also provided detailed instructions to censors tasked with inspection of the mail. Outgoing mail came to the censor unsealed, but incoming mail was to be “opened by clipping with scissors on the shorter side of the envelope.” All mail was to be read with an eye to prohibited content, with additional attention paid to the possibility of “secret writing”—even to a message written underneath the stamp—or “any unusual sign which might be a prearranged signal for a secret message.” Other things to watch for: differing ink colors; seemingly “pointless” content; traces of liquids or pastes to be harvested for invisible ink; and code in the form of letters, numbers, drawings, indentations or pinpricks above, below or through the writing. Photographs, of course, came in for the same scrutiny; nevertheless, the regulations advised, “Censors should use care in suppressing private prints, particularly in view of their value as keepsakes to personnel.” In addition to shears and razor blades, the weapons available to the censor included ink, prepared according to a special formula, for obliterating unacceptable content. Censoring ink, however, was to be used “only where deemed particularly advisable for casual indiscretions” in letters home.

Thomas Tichenor’s copy of the U.S. Navy’s censorship regulations is part of the Tichenor Collection in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more World War II collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.