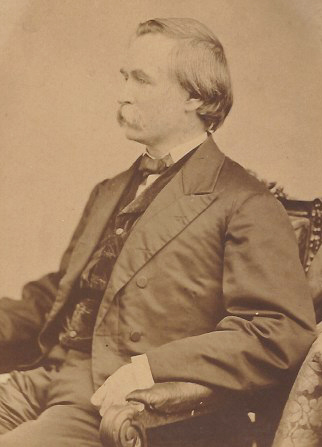

After her husband’s death in 1852, Maria Knott left her home in Lebanon, Kentucky for Missouri, where her son, James Proctor Knott, was beginning his legal and political career (Proctor Knott would later become governor of Kentucky). Five of Maria’s other children were also in Missouri, but late in 1860 Maria returned to Lebanon to visit her son William. She was caught there when the outbreak of the Civil War tore apart her family, her town and her country. Her letters and diaries, held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library, vividly record her conflicting emotions and experiences.

“In this cruel rebellion,” she wrote, “there is scarcely a family that is not divided”– her own included. Son William was against secession. Maria’s Missouri children, however, were less enamored of the Union. Though not “secesh,” son Proctor, then Missouri’s Attorney General, would lose his position after balking at what he believed was a heavy-handed loyalty oath to the United States. Proctor’s wife (and first cousin) Sallie needled William for his “tory” sympathies and took delight in calling herself a “rebel.” When William was briefly taken prisoner after secessionists captured a rail car in which he was traveling, Maria complained angrily that some of his uncles would not have “raised a finger” to rescue him.

In the face of growing violence, middle ground was hard to find. “I don’t like Lincoln any more than you,” Maria admitted to Sallie about the recently inaugurated president, but “don’t condemn him for what the south has brought on us.” Secret, pro-slavery cabals like the Knights of the Golden Circle had seized on the interregnum between Lincoln’s election and inauguration to initiate a rebellion. Now, Maria observed with distaste, “I am told all the respectable portion of society belongs to the secession party,” yet lawlessness prevailed and citizens were being “driven from their homes on account of their principals [sic].”

Trying to sort rumor from fact, Maria followed news of the war closely, and observed firsthand its effect on Lebanon. She was saddened by the hardships of Union soldiers passing through the area – encamped in cold and rain, sick with measles and smallpox, and dying far from home and loved ones – but despaired at their demands on the local population as they appropriated precious food, water, livestock, timber, horses, wagons and mules to meet military needs. “Joy go with them,” she wrote wearily, but “I for one will be glad to see the last one leave.” The threat of Confederate incursions caused unbearable anxiety. “We are to be murdered and burnt by the rebels who are approaching,” Maria cried after they captured Lexington and Frankfort in mid-1862. She reserved special animus for Confederate guerrilla John Hunt Morgan – that “child of satan” – who tormented Lebanon with destructive raids in 1862 and 1863. In September 1862, with the town full of “secesh soldiers,” she pronounced members of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s “rebel Cavalry the dirtiest most woebegone looking set of men I ever saw.”

“God only knows what is to be the result of this war,” Maria often lamented, but she would never know, for she died on March 6, 1864. From the beginning of the conflict, however, she maintained that her “once happy united states” would be irreparably changed as some, including many in her own family and community, foolishly staked their futures on “destroying the best government that ever was made.”

Click here for a collection finding aid and for typescripts of Maria Knott’s letters and diaries. For more of our Civil War collections, click here.