On May 14, 2016, the Bowling Green Daily News ran a story about James Minor “Jimmie” Stewart, a 99-year-old World War II veteran who spent more than two years as a prisoner of war in Germany. The story highlighted Stewart’s “wartime log,” a journal issued by the Red Cross that invited POWs to document their experiences with diary-style entries, drawings, poetry, and keepsakes. The objective was to create a “permanent souvenir” that would serve as a “visible link” between the soldier and “the folks at home.”

While we are sorry to report Jimmie’s death on April 26, 2017, we are very pleased that his wife Ruth has recently donated his wartime log to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. It is both a poignant and inspiring record of Stewart’s life behind barbed wire.

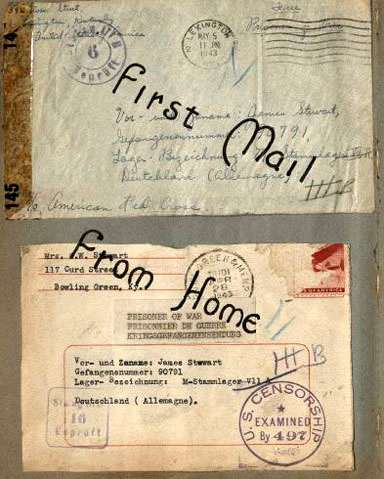

These hardcover journals were somewhat bulky, and many soldiers shed them as unwanted baggage when they, like Jimmie, were moved around from one prison camp to another. But Jimmie took the volume’s instructions to heart. Included in his wartime log were poems, drawings, lists of his fellow prisoners, envelopes from home, German banknotes, and even an official military ballot from the 1944 presidential election.

Some of the content was created by Stewart in his meticulous hand, while some was added by fellow prisoners. In “Poems by P.O.W.’s,” contributors dream of freedom and of those waiting at home (especially mothers), mourn lost comrades, and warn draft dodgers to “keep away from my girl.” One poem recalls the aftermath of Sidi Bou Zid, a battle in Tunisia that saw a smackdown of American soldiers by more experienced German troops. Its author nevertheless mocked Hitler by using the name of his father, the born-out-of-wedlock Alois Schicklgruber, and promised revenge: So now we’re the guest / Of that Austrian pest / “Shickie” The boy with my heart / But our buddies are coming / To fix up his plumbing / Or maybe to take it apart.

Perhaps most surprising to see are the many photographs in the journal: of camp buildings, Stewart’s fellow prisoners, two young ladies of his acquaintance, and camp activities. When they were not put to work, the men found time to stage musical performances and South Pacific-style theatricals featuring comely fellows in wigs, dresses and five-o’clock shadows.

A loose flyer in the journal told of the approaching end for the Nazis in April 1945: stand your ground, it ordered soldiers who were thinking of putting down their weapons and scattering. For Stewart, fortunately, liberation came in May, then repatriation to Bowling Green, where his wartime log survives to tell his story to the “folks at home.”

Click here for a finding aid and full scan of James Minor Stewart’s wartime log. For more World War II collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.