Bevie W. Cain, 1844-1883

Bevie Cain was only sixteen when the Civil War broke out. Over the next few years, however, the Breckinridge County, Kentucky schoolgirl took time from her studies and social life to express her increasingly partisan opinions about the conflict.

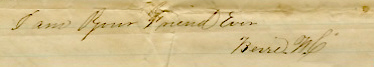

In a remarkable series of letters to her friend James M. Davis, Bevie warned him not to be too open about his Unionist sympathies. “Not one word would I write to an abolitionist knowingly. I would consider it an everlasting disgrace to myself,” warned the self-described rebel. After the Emancipation Proclamation freed Southern slaves, Bevie asked James “how you can still be for Lincoln.” The President’s acts as commander-in-chief drew further scorn. “Lincoln does a great deal of mischief under cover of ‘military necessity,'” she observed.

But Bevie Cain could also turn an unsentimental eye on herself and her society. She thought marriage a rather curious institution, often contracted for convenience above all else, and sometimes found the courtship strategies of her male friends tiresome. In one of her more petulant moments, Bevie expected “to be a school marm, if my education is ever sufficient — if not I will live and die a happy ‘old maid’ hated by all and loving none in return.” Clearly, Bevie was a rebel in other matters besides the Civil War.

A finding aid for Bevie Cain’s letters, available at WKU’s Special Collections Library, can be downloaded here.

Good life is the most important.

Very interesting to read. I enjoyed well while reading. I will recommend my friends to read this one for sure.

This is very teaching. My mom used to tell me about this, how grandma would talk to her about the civil war. It can get pretty touching. Here’s to Bevie Cain