Theresa Rajack-Talley, Associate Dean for International Diversity and Community Engagement Programs in the College of Arts & Sciences at the University of Louisville, was featured in our WKU Libraries’ Far Away Places speaker series on Thursday, March 22, at Barnes & Noble Bookstore in Bowling Green, KY. The focus of her talk was also the title of her book Poverty is a Person: Human Agency, Women, and Caribbean Households. A book signing ensued in conclusion of her talk.

Monthly Archives: February 2018

Far Away Places presents Theresa Rajack-Talley, author of “Poverty is a Person”

Comments Off on Far Away Places presents Theresa Rajack-Talley, author of “Poverty is a Person”

Filed under Events, Far Away Places, Latest News, People, Podcasts

Kentucky Live! presents Timothy B. Smith, “Altogether Fitting and Proper: Civil War Battlefield Preservation in History, Memory, and Policy”

Timothy Smith from the University of Tennessee at Martin was the featured speaker in WKU Libraries’ “Kentucky Live series” on Thursday, March 8, at Barnes & Noble Bookstore in Bowling Green. His topic was “Civil War Battlefield Preservation in History, Memory, and Policy.” The talk concluded with book signing.

Comments Off on Kentucky Live! presents Timothy B. Smith, “Altogether Fitting and Proper: Civil War Battlefield Preservation in History, Memory, and Policy”

Filed under Events, General, Kentucky Live, Latest News, People

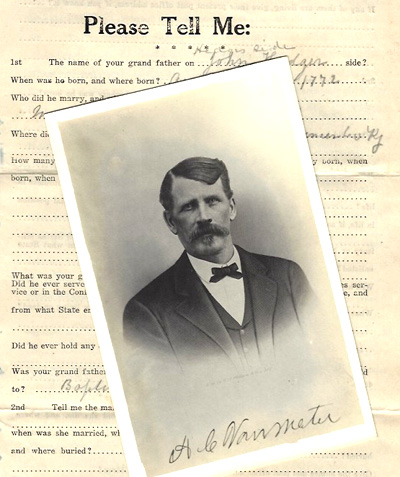

“Please Tell Me. . .”

It was a gargantuan undertaking, but for decades Jackson Clinton Van Meter (“J.C.”) labored toward his goal: to compile a history of the Van Meter family in America. The old Dutch clan gained a foothold in the New World in the 17th century, when pioneer Jan Joosten Van Meteren arrived with his wife and five children and began to accumulate property in New York and New Jersey. By the early twentieth century, J.C. estimated that there were about 20,000 Van Meter kinfolk to track down.

From his Edmonson County, Kentucky home, J.C. searched diligently for Van Meters and members of related families, sending letters to them all over the country and asking them to supply detailed information about their ancestry. “Please Tell Me:” was at the head of his preprinted, fill-in-the-blanks questionnaire that asked the subject to begin with his/her grandfather and supply names, dates, birthplaces, occupations, professed religion, marriages, children, and so on. J.C. would also type out tailor-made questionnaires, particularly where he was in need of certain information or the recipient had failed to supply a full genealogy. New contacts gleaned from one subject would lead to a fresh round of letters and questionnaires. In addition, J.C. vacuumed up data from other researchers of the same family lines and incorporated it into his collection.

To encourage his subjects to participate, J.C. had a unique selling point: somewhere back in the mists of time, the Van Meter family had married into the mysterious Hedges family. Legend had it that one Charles Hedges died in England leaving some $269 million to a nephew who had emigrated to America. The inheritance lay unclaimed in the Bank of England while the Van Meters and Hedges multiplied across the ocean, but J.C. theorized that if all the present-day heirs could be proven and the results presented to the Bank, the massive fortune could finally be distributed.

Hmmm. We’ve seen this before. And while we can’t conclude that J.C. believed the Hedges estate to be genuine (it wasn’t), it still allowed him and many, many Van Meters to fantasize about hitting the jackpot…and, incidentally, it generated a mass of genealogy, now held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more family research collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

Comments Off on “Please Tell Me. . .”

Filed under Manuscripts & Folklife Archives

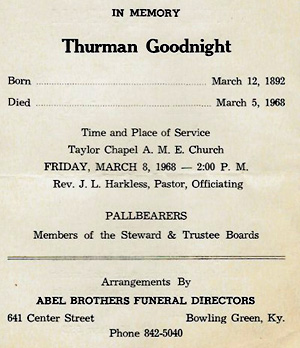

Abel, Boyd, and Kuykendall

In 1900, James E. Kuykendall (1874-1960), an African-American native of Butler County, Kentucky, opened a funeral home at 819 State Street in Bowling Green. For more than 50 years, he served the city’s African-American population both alone and in partnership with James A. Boyd. In the 1930s, brothers Francis and Richard Abel established Abel Brothers, which also served the same constituents.

The records of these historic African-American businesses were later placed with Gatewood and Sons Funeral Chapel, and copies are held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Dating from 1900-1970, they provide data about funeral dates and expenses, but some are useful genealogical resources because they provide additional information about the deceased such as occupation, cause of death, parents’ names, and place of interment. Also included with these records is a listing of interments in Mt. Moriah, Bowling Green’s African-American cemetery.

A finding aid for these funeral home records can be accessed here. For more collections on funeral homes and other businesses, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

Comments Off on Abel, Boyd, and Kuykendall

Filed under Manuscripts & Folklife Archives

Sophia

She was, by his description, a “little mulatto girl” he first encountered in 1867 during his military duty at Little Rock, Arkansas. Their ensuing 22-year relationship was neither simple nor ordinary, but the story of Sophia and Captain Richard Vance, a native of Warren County, Kentucky, is preserved in Vance’s diaries, now part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. The only thing missing from the story, sadly, is the voice of Sophia herself.

Separated from her family and cast adrift after her emancipation from slavery, Sophia, no more than sixteen years old, seemed doomed to become the sexual plaything of the officers in Vance’s garrison. Indeed, that may have been how Vance himself, who frequented local prostitutes to satisfy his need for a woman’s “delicious embraces,” initially regarded her. But he soon found himself “desperately stuck on my little girl”– my “new flame”– and when Sophia’s principal patron abandoned her, she became his servant and mistress.

Though completely smitten, Vance was fearful that his “dangerous experiment” would be discovered. Nevertheless, neither he nor Sophia were inclined to end the relationship, and he was relieved in 1869 when he managed to bring her along to his new posting at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In 1876, they were at Fort Dodge, Kansas, where Sophia married and departed, Vance assumed, for a new life. Before long, however, both Sophia and her husband George returned and took up the care of his household. Throughout Vance’s subsequent duty in the Indian Territory, Colorado and Texas, they turned his military lodgings into a comfortable home, anchored his life, and eased his restlessness and unhappiness with the Army. When Henry, a young boy abandoned to Sophia’s care, joined the household, an odd but strangely durable family unit was created.

Everything changed late in 1888, when Vance returned to Fort Clark, Texas from a lengthy trip to find Sophia ill. He had been wearily searching for a place to retire and had even purchased a farm near Washington, D.C., but was torn between bringing Sophia, George and Henry into his post-Army life or making a clean break. Only after watching in anguish as Sophia sank and died in May 1889 did he understand what he had lost. His diary entry cried out simply: I am in a world of trouble. Sophia.

Wandering from place to place in retirement, Vance routinely turned his thoughts back to his years with Sophia. “Those were my best and happiest days,” he wrote, “the like of which I must not expect to see again, for there was but one Sophia.” On a January morning in 1893, he found the scene outside his lodgings so reminiscent of “the prospect from the back window of the last quarters I occupied in Ft. Clark that I can easily fancy that I have but to go below to find Sophia busying about some household duty; to find Henry playing with his toys in the yard; to find the dogs lazily dozing in the wood shed; and all the paraphernalia of my old establishment.” For Vance, who never married, Sophia represented a golden age that he had failed to appreciate and to which he could never return.

Click here for a finding aid to the Richard Vance Collection. For more collections search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

Comments Off on Sophia

Filed under Manuscripts & Folklife Archives