On this World Mental Health Day, we look back to 1872 when, in the absence of systematic treatment or medication, an ordinary woman tried to cope with depression.

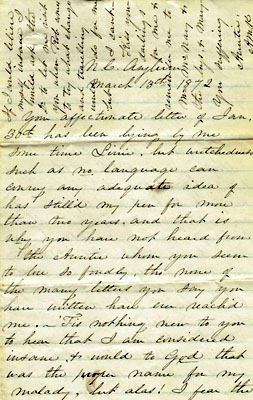

On March 13, 55-year-old Anna Mary Kirkland wrote from North Carolina to her niece Eliza “Lizzie” (Edmunds) McNary, who as a girl had moved with her family to Caldwell County, Kentucky. Anna apologized for the long drought in her correspondence, “but wretchedness such as no language can convey any adequate idea of has still’d my pen for more than two years.” She had entered the North Carolina Asylum, but knew it wasn’t the right place: “I am considered insane & would to God that was the proper name for my malady, but alas! I fear the case is a far sadder one than insanity, tho’ that is sad enough.” Stalked by obsessive thoughts about her “lost” soul and those of her children, Anna bewailed the state of “living death” she could not overcome.

Well-meaning family members had tried act as armchair psychiatrists, but Anna explained that her “periods of darkness” were unresponsive to “human reasoning and eloquence” or to the theory that they were merely “insane delusions.” She confessed that Lizzie’s news of her husband and children had made little impression: “Were I not so wretched your good accounts of the dear boys would please me so much & I would be so much interested. . . as it is I can’t take an interest in anything.”

Anna managed to convey a few items of her own family’s news, but returned to the notion that a diagnosis of insanity might actually help her come to grips with her paralyzing burden. In that case, she wrote, she could even believe herself capable of visiting Lizzie, of experimenting with travel and change. . . “but I can’t.”

Anna’s letter is in the Edmunds Family Papers, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.