I have got me a leg, made by Mr. Mccartey of milledgville, it cost ten dollars, your uncle james got it for me. . . .

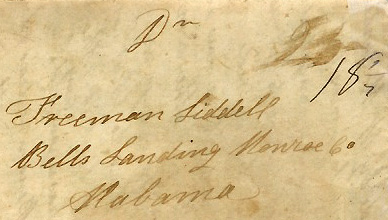

So declared Moses Liddell of Gwinnett County, Georgia, in a letter to his son Freeman written on March 2, 1841. The senior Liddell, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, filled the first several paragraphs of his letter with admonitions to his son to follow a path of uncompromising Christianity. Worried that 25-year-old Freeman, a physician who had moved to Monroe County, Alabama, might fall victim to the “sin and infidelity” rumored to afflict that region, he assured him that “we have not ceased to Pray dayly for you.”

With respect to his new prosthetic leg, Moses seemed less concerned that it might fall by the wayside. “I fear whether it will profit me much, I can get about so much better with out it, that I dont use it enough to get use to it,” he wrote. Like many amputees, he had refused to allow his disability to inhibit his favorite pastime. “I do almost any traveling on horse back, I love to ride mightily,” he reminded his son. No doubt 21-year-old “Jinny,” his “constant rideing nag,” had also adapted to her master’s missing limb.

The letter, nevertheless, hinted at the trauma of the amputation itself, especially the impression it left on Freeman’s youngest sister, 3-year-old Nancy. Presented with a gift, reported Moses, “she was very much overjoyed.” But when she learned the present was from her big brother “Dr. Liddell,” she would have nothing more to do with it. “She cant bear the name of a doctor,” explained her father. “She says you cut off my leg, she ha[s] forgotten you.”

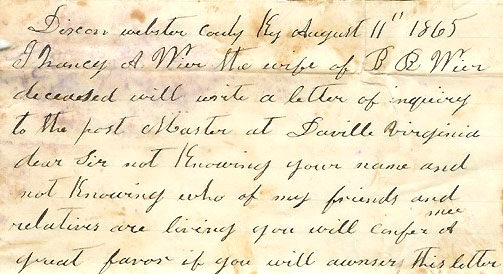

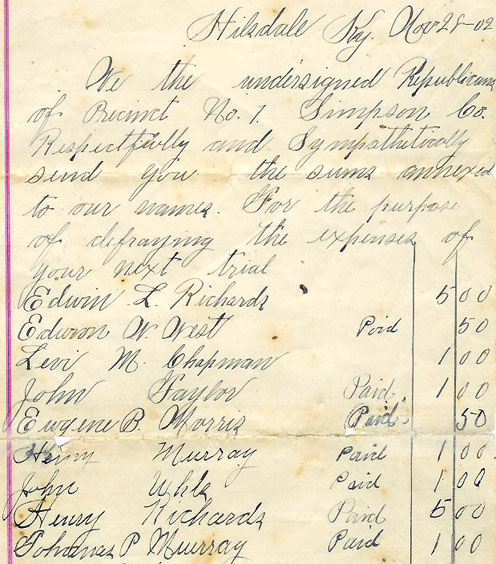

Moses Liddell’s letter is part of the Parker Family Collection, housed in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives unit of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.