Like his three brothers, Romanus Emerson (1782-1852) seemed destined for the ministry, but a speech impediment sent the New Hampshire native instead to work as a carpenter and merchant in Boston. A cousin of transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, Romanus remained a devout Baptist until his 50s when, under the influence of Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason and his own freethinking nature, he washed his hands of all religion and became an atheist – in his word, an “infidel.” His self-composed funeral oration condemned theology as “a system of deceit and fraud” and exhorted his survivors to get a good education, observe the golden rule, and accept that “there is no part or parcel of the creature man that survives his decomposition.”

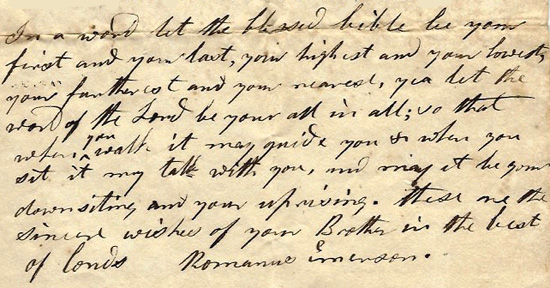

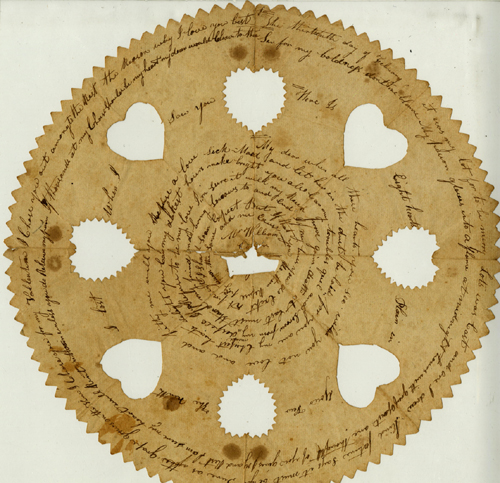

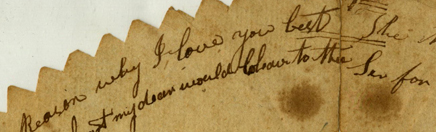

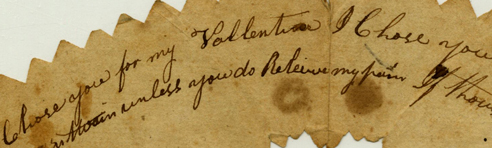

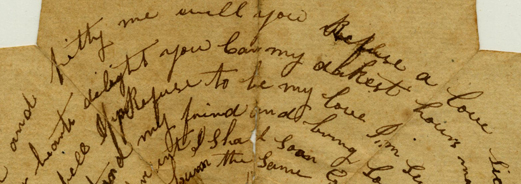

But Romanus was still a believer in 1822 when he and his wife Jemima wrote to 33-year-old Fanny Goodridge, who had left Boston to teach school in Lexington, Kentucky. Jemima was interested in sharing news and hearing of Fanny’s “sorrows and joys,” but was also anxious about her new life “amungst strangers” and hoped that after serving the next generation “in that place,” she would return safely to her “native land.” Romanus, on the other hand, wrote in full lecture mode, instructing her to remain pious above all else and never to lose sight of God. “Let the blessed bible,” he urged, “be your first and your last, your highest and your lowest, your furtherist and your nearest . . . your downsiting and your uprising.”

Even if Romanus ended up disowning his own advice, Fanny stayed the course. A year later, she began a Sabbath School in Michigan, and a few years after that emigrated with her new husband to Kansas, where they spent most of their lives as missionaries and teachers among the Potawatomi Indians.

Romanus and Jemima Emerson’s letter is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.