It was a September day in 1880, and 20-year-old Cartmell Huston was bored. Her brother had asked her to keep him company at his dull bank job in Uniontown, Kentucky, and after passing the time poking through desk drawers and watching customers enter a next-door restaurant, she grabbed some counter checks and started filling them out in “fabulous amounts to see how folks feel who have bank accounts.” She wrote one for $25,000 and enclosed it in a letter to her friend, Clarence McElroy of Bowling Green.

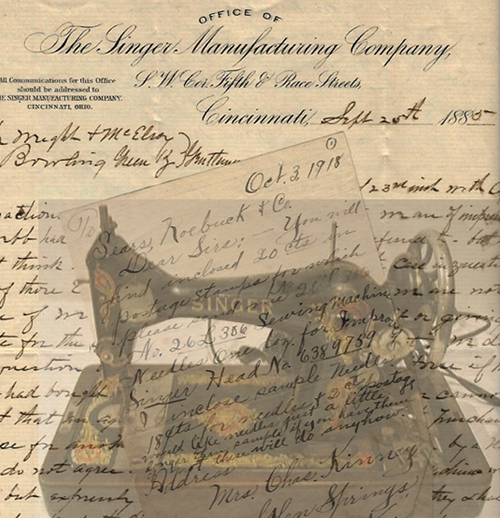

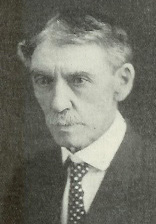

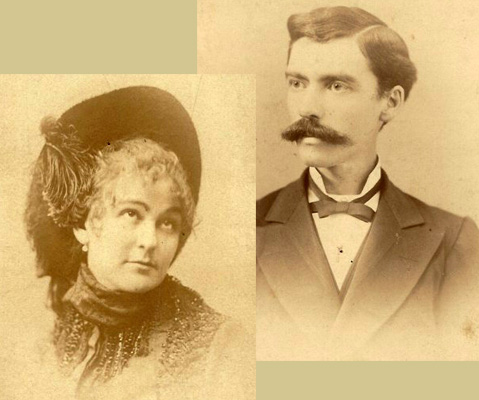

It’s unclear where or when, but Cartmell, the daughter of a prominent Morganfield, Kentucky judge and banker, first laid eyes on McElroy, a 31-year-old lawyer and state legislator, from across a ballroom where she stood trapped by a “dreadful bore.” They struck up a kind of courtship—one which, not unusual for the time, was carried on largely through correspondence. We don’t know if Cartmell kept his letters, but McElroy kept hers, secreted among a large collection of his legal files now in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. They offer an intimate portrait of Cartmell: perceptive, wryly intelligent and literate (her sister was the novelist Nancy Huston Banks), yet a restless young woman who found herself with nothing much to do except wait for someone to propose marriage.

In the meantime, Cartmell puttered about at home, read widely, learned music, helped entertain her parents’ friends, visited, walked with her sister, went to picnics and dances, observed the courtships of her girlfriends, and devoured McElroy’s letters. When he would not match the frequency of her correspondence or its emotional openness, she complained—“You are so unkind to me, I do not see why I want you to like me or why I do not accept the utter indifference you are at no pains to conceal”—but when a “pleasant letter” arrived afterward she found it hard to maintain her resentment.

Then the clouds would gather again: “I do not deserve that you think so well of me,” she told McElroy. “For when I think of the sameness of my life, I feel disinclined to take up a belief in its sacredness, or that it has any responsibility than to laugh at its own failure. At some times I have felt within me the capability for higher things—but mostly I feel—nothing—save a slow discontent—a dull dislike of the duties of my quiet home.” Nevertheless, she wrote, “it is the one great relief I have, to bring all my disappointments and cares and moods to you, and to be always sure of your sympathy and a patient hearing.”

When that fateful proposal did come—but not from McElroy—Cartmell conveyed the news with barely concealed anguish. Having previously dropped hints about the matter, she finally informed McElroy in December 1880 of her marriage “the last of this month to Mr. Bishop of Cincinnati, with the provision of course, that I’m not dead before then.” Was McElroy surprised? she asked. “I don’t mind confessing to you, that I was myself, a little—just at first.” She had known Bishop for four years, however, “and I always half way believed I would marry him.” It was a daunting prospect—“I am giving up all control of my life and happiness,” she declared—but he was a good man who loved her despite knowing she was “impractical and unreasonable,” and she was going “to try as far as is in human power to make him happy.”

But then regret flooded over her, unconcealed from the friend who knew “so much of my inner life.” She admitted that the home that had wearied her with its “quietness and sameness” was not, in fact, “the cause of my disquiet”; rather, it was that she had not summoned McElroy there to talk about her deepest feelings—“about that subject that I could not write to you of.” But time had run out.

McElroy’s reply threw Cartmell into utter despair. Why didn’t you write this letter to me two months ago—or why in God’s name did you write it at all? she cried. If I had believed you cared—now, when it is too late to affect our lives, when it will be a confession of no moment to you, a confession of shame to me—still I brave all things—dare all things—and tell you the truth—that I love you I love you. I would lay down my life for your happiness—I never have loved any one but you—I never shall—and now it is too late—too late. God help me.

On December 29, 1880, Cartmell married Roland P. Bishop. In 1887, they moved to Los Angeles, where Bishop, as a principal of Bishop & Company, a food and confectionery manufacturer, would become one of the leading businessmen of southern California. The move, however, may have been originally prompted by Cartmell’s health, for she died in 1891, aged only 30.

Click here for a finding aid to the Clarence Underwood McElroy papers, which include Cartmell Huston Bishop’s letters. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.