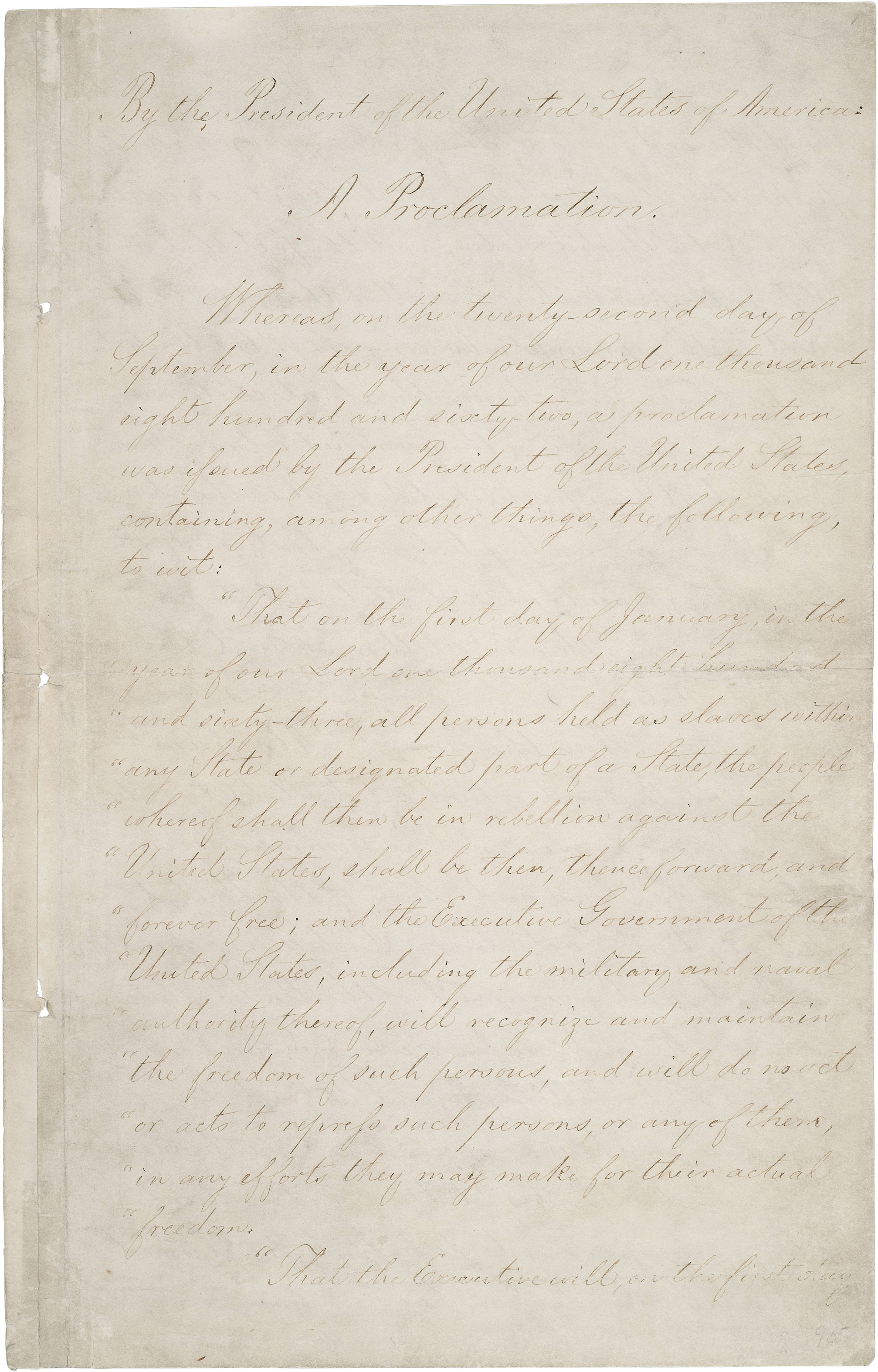

On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln placed pen to paper and wrote the following executive order,

(Courtesy of the National Archives)

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

As an authoritative wartime measure, the Emancipation Proclamation granted freedom to more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans who remained under control by the Confederate government in ten southern states—not including the “border states” and those already under Union occupation.

While the proclamation, which was contingent upon a Union victory, may have ignited a firestorm of criticism from white southern sympathizers and praise from anti-abolitionists, its implementation was slow to take root, especially in Texas.

Seceding from the United States on February 1, 1861, Texas became the fourth state admitted into the Confederacy. Throughout the course of the Civil War, slaveholders from eastern states, notably Arkansas and Louisiana, routinely brought slaves to Texas in order to avoid emancipation, which significantly increased the number of slaves across the state. When the Emancipation Proclamation was made official in 1863, however, it took nearly two and a half years before the order was enforced. While theories abound in order to explain this severe lag—ranging from murder to deliberate miscommunication—history itself is quite clear.

On June 19, 1865, Union Army General Gordon Granger and his troops landed on the beaches of Galveston Island and declared Texas under federal occupation. Granger read Lincoln’s executive order, thereby liberating the nearly 250,000 slaves living in Texas. “Juneteenth,” then, has come to be recognized as the “traditional end of slavery in Texas.” The day has become established as a state-recognized holiday, while other states may observe Juneteenth in other forms of ceremonial remembrance. The underpinnings of Juneteenth rest on the celebration of Black pride, solidarity, and cultural heritage.

Akin to Juneteenth festivities, the 8th of August is another emancipation-related holiday observed by African American communities in both western Kentucky and Tennessee. While the reasons for celebrating August 8th remain unclear, the lasting impact it has had on the region is decidedly obvious. Every year, the city of Paducah, Kentucky hosts its 8th of August Homecoming Emancipation Celebration. The Homecoming seeks to honor exceptional members of the African American community, both past and present, through memorial services, picnics, music performances, and church assemblies.

WKU’s Manuscripts and Folklife Archives contains a collection (FA 635) of materials gathered together from Paducah’s 2008 8th of August Homecoming Emancipation Celebration titled “A Journey by Faith.” In his program introduction, Robert Coleman, President of the W.C. Young Community Center Board of Directors, writes,

“America’s struggle, rise, and triumph from slavery to equal rights for all is a living testament to the power of deep, personal faith for Americans of all colors. That deep well of faith from the darkest days of slavery sets the African American experience of religion apart.”

The program itself includes articles describing the accomplishments of distinguished members of the Black community, advertisements for local businesses and churches, and a schedule of the weekend’s events. The collection also contains photographs of the celebration, vendor information, business cards, and two interviews with James Dawson, a member of the First Liberty Missionary Baptist Church, that were recorded on digital videocassette tapes.

For more information on African American folklore, material

culture, foodways, and achievements throughout the state of Kentucky and beyond,

visit TopSCHOLAR

or browse through KenCat,

a searchable database featuring manuscripts, photographs, and other non-book

objects housed in the Department of Library Special Collections!

Post written by WKU

Folk Studies graduate student Delainey Bowers