Born in Virginia, Stella Godfrey White was educated in New York and Cleveland. A schoolteacher and social worker, she served in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II. After the war, she moved to Cleveland and married Charles W. White, a Nashville native. Both were civic servants and community activists. Stella was the first woman appointed to the board of the Cleveland Transit System and her husband, a Harvard law graduate whose career began slowly because no law firm would hire him, became Ohio’s first African-American common pleas and appellate judge.

Warren County, Kentucky native Harry Jackson also found himself in Cleveland after his war service. As director of public relations for a chemical manufacturer, he became involved with many community boards, cultural organizations and other beneficiaries of his employer’s charitable foundation. It’s likely he and Stella White regularly crossed paths in the course of their community work and at Trinity Cathedral, where they both attended church.

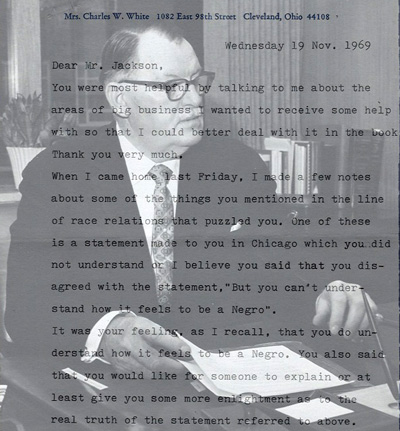

In 1969, White was beginning a four-year stint as a columnist for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, writing on race and class issues. She and Jackson got to talking about race relations, and he related an incident in Chicago, where a young man once told him “You can’t understand how it feels to be a Negro.” Puzzled, the 62-year-old Jackson had wished for some “enlightenment as to the real truth of the statement.”

“I have thought quite a bit about just how I could try to help you understand what that young man meant,” White wrote Jackson in a letter dated November 19, 1969. She offered this example:

You are a tall man and I’d like for you to try to imagine waking up one day in a strange place where everything was scaled to accommodate only people who are five feet tall. Every doorway is too low for you to pass through without stooping. Every table is too low . . . . All of the clothing is made to fit the people who live in this hypothetical place. You get a jaywalking ticket so you must appear in court. The judge is prejudiced because you are not the same height as all of the rest of the people. . . . You draw a jail sentence and all cells, etc. are to the five foot scale . . . .

During this prolonged period of utter frustrations, you find yourself unable to find anyone who will listen to your complaint . . . . You were made to feel that you mattered so little to others that you began to matter not at all to yourself . . . . When you finally escaped you had to begin to lift yourself from the depths of self-hate which had engulfed you because you had been so blatantly hated. . . . You had to begin to find yourself. . . so that you could establish for yourself dignity and respect. . . .

No matter how hard you tried, other people found it hard to understand your predicament. . . . Not a soul, no matter how sympathetic could understand how you felt, because none had experienced being a tall man in a land of prejudiced, discriminating five footers.

Thank you for being my friend. Sincerely, Stella G. White

Click here for a finding aid to the Harry Jackson Collection, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.