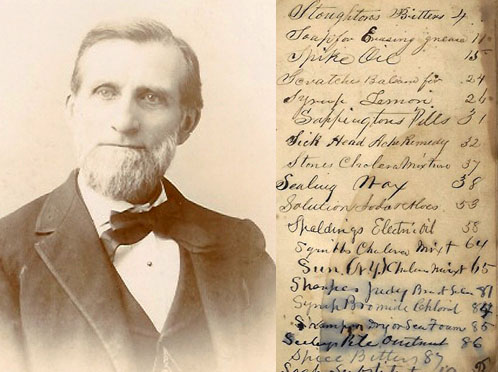

When John E. Younglove (1826-1917) came to Bowling Green in 1844, the town gained a curious and inquiring citizen. Over his long life as a druggist, town trustee and cemetery commissioner, Younglove collected rare books, archaeological specimens and tales of local history. He also collected weather.

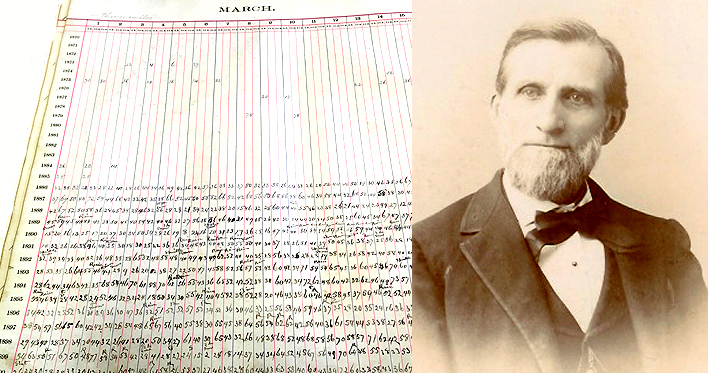

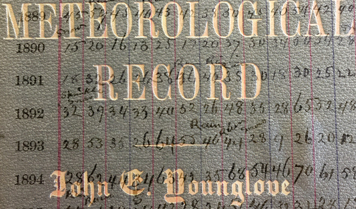

From 1849-50 and 1851-52, Younglove kept daily records of temperature (four readings a day), “clearness of the sky,” wind, and clouds. A member of a national network of volunteer observers, he forwarded his data to the Smithsonian Institution for use in its new meteorology program, then tackling “the problem of American storms” and how to predict them.

Younglove added other remarks to his notations, usually concerning the intensity of rainfall. But his entries for June and July 1849 included another phenomenon that deserved close attention. Early in the year, a wave of cholera had begun to make its way from India and across Europe. Everyone knew that it would soon arrive in America – and that the nation was unprepared. On June 9, 1849, Younglove’s weather notes recorded three deaths from cholera, “the first we have had.” In a month characterized by high heat and excessive rain, the steady drip of deaths continued: one on the 14th, one on the 19th, two on the 22nd, five on the 23rd, and so on.

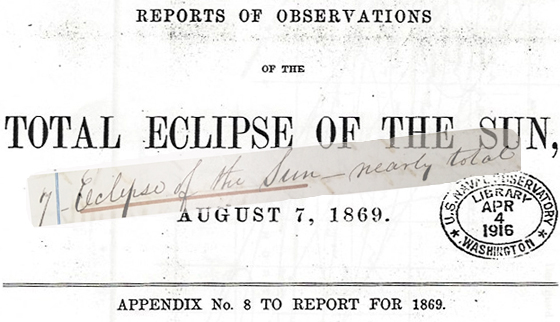

Younglove’s record-keeping grew less frequent until 1886, when he resumed in earnest. Through 1901, he filled his ledger with four-times-daily temperature readings, kept for the Department of Agriculture’s Climatological Service. In addition to contemporary records, he preserved stories of weather and atmospheric phenomena gathered from his own experience and that of old-timers: the reverberations of the 1811 New Madrid earthquake; a magnificent meteor shower in 1833; the 18-below-zero day in February 1835 and the 24-below-zero chill in January 1877; the total eclipse of 1869; an 1870 tornado that destroyed Cave City; the 28-inch snowfall that buried Bowling Green in February 1886; and various record-breaking storms, killer frosts, locust infestations and river rises. When an even deadlier visitation of cholera arrived in 1854, courtesy of the infected members of a travelling circus company, Younglove suspected that the outbreak was made worse by heavy rainfall during a performance “which caused the steam to arise” inside the crowded tent. His chronicle was wide-ranging and unique: in annual narratives covering 1870 through 1909, Younglove looked back on each year’s weather patterns as they brought prosperity or hardship to the gardeners and farmers of his community – and formed a backdrop, in a few cases, to serious public health crises.

John E. Younglove’s meteorological record is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid and scan. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.