With the upheaval of the Civil War still a year away, Hattie Binford of Hickman, Kentucky was preoccupied with a smaller, more personal and yet equally consuming drama: the man who got away. Perhaps because her friend Lucy (Parker) Robbins was 10 years older and married, 17-year-old Hattie looked to her for mentorship on matters of the heart.

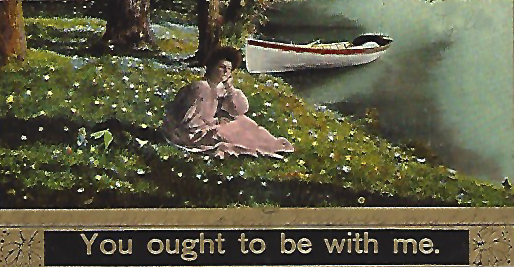

Hattie had just experienced a sighting of the object of her affection, a certain “Mr. McBride,” she wrote Lucy in May 1860. Unfortunately, her glimpse of him was as “the Bridegroom of another. I had to summon all the courage and fortitude I possibly could to keep from showing my feeling,” Hattie mourned, “which was not very pleasant at that time I will assure you.” But she vowed to rebound. “There is as good Fish in the sea as ever was caught out so I will have the pleasure of catching another.” For instance, that gentleman presently staying with Lucy, what was his name? “Let me know if he is a candidate for matrimony,” Hattie demanded, “he can have my vote.”

Hattie filled her letter with other local news, including a visit from two admirers, but “I think I can do better than to take either of them.” Her gold standard remained Mr. McBride, and she deputized her friend Lucy to “pick me out a nice Beau.” He didn’t have to be rich, as long as he didn’t drink whiskey and play cards (to excess, that is). “I want the jewel to consist of himself,” Hattie wrote dreamily. “I want him to be handsome intelligent polite good natured,” as well as modest—“no profusion of fob chains Necktie or big words need apply, for they cannot fill my Eye.”

Click here to download a finding aid for Hattie’s letter, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For other letters about courtship and marriage, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.