Across the broad continent of a woman’s life falls the shadow of a sword. On one side all is correct, definite, orderly; the paths are straight, the trees regular, the sun shaded; . . . she has only to walk demurely from cradle to grave and no one will touch a hair of her head. But on the other side all is confusion. Nothing follows a regular course. – Virginia Woolf

How can one not wonder about the history of a woman named Sunshine? And yet the conventions of 19th-century femininity made it hard to know women, even one with a name like that.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky to Bavarian immigrants, Sunshine Friedman was the baby of her family. In 1878, when Sunshine was six, the Friedmans moved to Paducah, where her older brother Joseph had convinced his father to join him in his vinegar manufacturing business.

As she grew up, Sunshine filled her high school autograph book with the scribbles of affectionate friends and relatives, including this one:

Sunshine Friedman is your name

Single is your station

Happy will be the man who

makes the alteration.

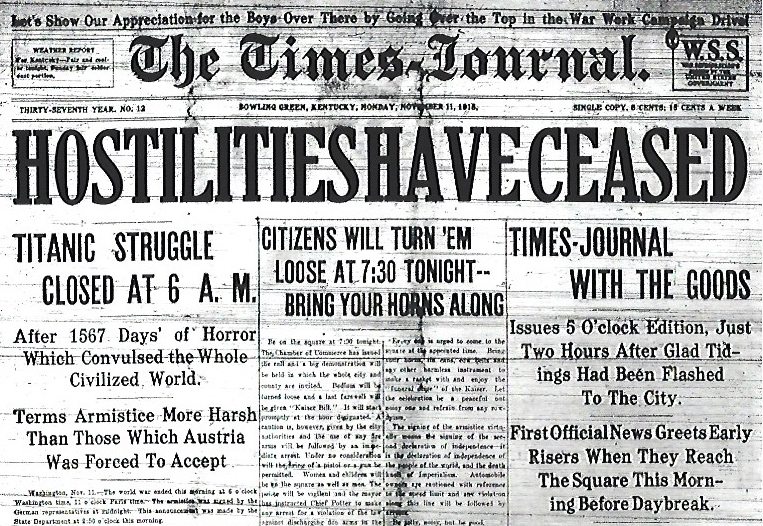

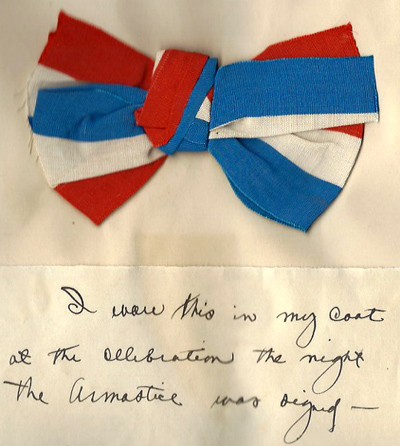

And by any standard, “Sunny” made a good marriage. In 1892, she wed Max B. Nahm of Bowling Green, a Princeton law graduate and clothier who would become a wealthy bank executive and a leader in the movement to establish Mammoth Cave as a national park.

From the commodious Nahm home on College Street, Sunshine reigned. By one account, she was “an active volunteer in numerous community organizations, a whiz of a bridge player, and the epitome of a dignified, Victorian lady.” But those Victorian values were painfully tested by Sunshine’s only child, Emanie, born in 1893.

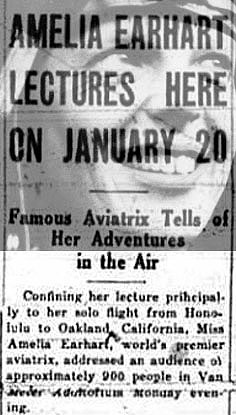

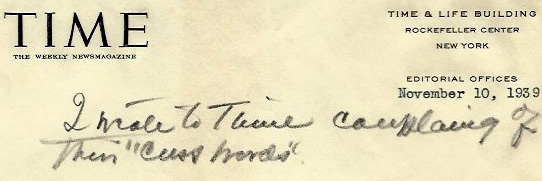

For better or worse, it was Emanie (far more open about her personal history than her mother’s generation) who tells us most of what we know about Sunshine. Clever, tomboyish in her youth, unconventional, and given to creative pursuits like writing and art, Emanie complained that her mother tried to suffocate her aspirations, warning her that men don’t like that sort of thing. Her parents took her to the New York theater every year, she remembered, but no other visual arts were on the agenda. The Nahm house was filled with books, but again, no pictures of any consequence. Her mother “wanted to tell me what to do,” Emanie groused, in stream-of-consciousness notes left in her papers. Though intimidated by this maternal presence, Emanie apparently reproduced it in her relationship with her own daughter.

And yet the women seem to have remained on good terms. Emanie left for New York, married, divorced, and enjoyed success as a writer and artist. Sunny traveled and took cruises with Emanie and her granddaughter, but by the 1930s heart disease was threatening to cut her life short. When Sunny died at 63, her friend Martha Potter watched rather uncomfortably as Emanie distributed her mother’s possessions. Martha received “her purple, velvet-jacket evening gown and a black coat suit with fox fur shoulders.” Seven months later, after lunching with Max (who outlived Sunshine by 20 years), Martha could only say, “We do miss Sunny very much.”

For more about the Nahm family in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections, click on the links or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.