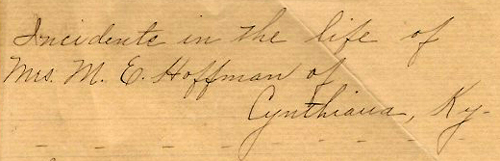

If it wasn’t for her five children, perhaps she would have tried to enlist, disguised as a man. Although Mary Elizabeth Hoffman never joined the unique ranks of such warriors, she didn’t allow her sex to defeat her personal crusade on behalf of the Confederacy.

Born in Boyle County, Kentucky in 1825, Mary saw her husband William, a son, and three brothers enter Confederate service during the Civil War. At home in Cynthiana, Mary jumped into the fray, delivering food, messages, aid and comfort to local rebels. Though auburn-haired and fair-skinned, she often managed to pass through Union lines posing as an African American. When some Confederate soldiers at a nearby hotel were cut off from their command and in danger of capture, Mary secured their horses, removed the incriminating weapons and uniforms from their saddle bags, and with the help of another Southern sympathizer later reunited the gear with its owners.

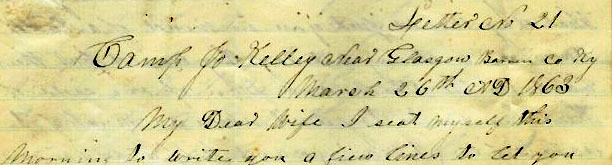

In April 1862, Mary resolved to head south to check on the welfare of her soldier menfolk, an undertaking that involved passing through numerous blockades and towns under martial law. With a stash of letters concealed in her clothing, she was denied a pass at Chattanooga, but wagered the commandant in charge that she would get through anyway. She did, by way of a midnight boat trip and a mule ride over mountainous terrain. When she arrived at her husband’s camp, she spent several months ministering to his wounded comrades. On the way back, she earned a pass from the commandant she had outwitted on the trip down.

In February 1863, however, Mary was arrested in Lexington and detained by the federals. Once again, she donned a disguise, climbed out a second-story window, and escaped. The Yankees caught up with her again and sent Mary and her husband, now discharged from service, north of the Ohio River where they would presumably make less trouble. They were eventually paroled and returned to Cynthiana, where Mary’s husband met an early death after an altercation with a Union soldier and Mary, who died in 1888, would be remembered as a determined soldier of the South.

Click here to link to a collection describing the exploits of Mary Hoffman, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to browse all of our Civil War collections, or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.