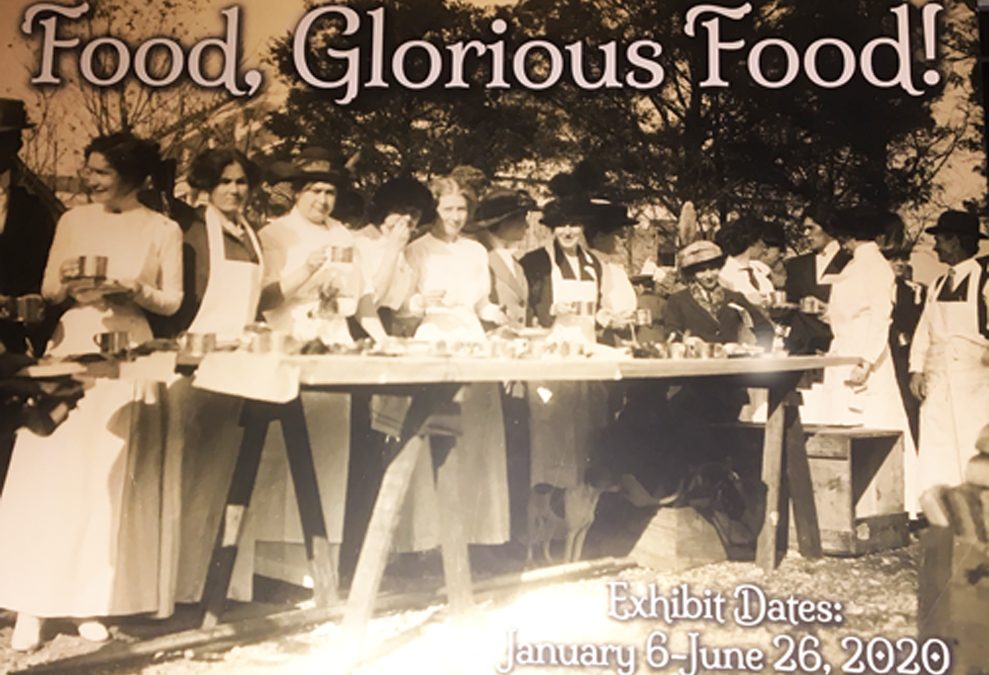

Food is one of the necessities of life. It is no surprise that Library Special Collections—which documents the Commonwealth’s culture—has quite a few items related to food. To celebrate this culinary material, an exhibit titled “Food, Glorious Food!” has been installed in the Jackson Gallery, on the second floor of the Kentucky Building. The exhibit will run through June 26.

Each case within the exhibit represents different aspects of Kentucky’s culinary heritage. Chief amongst the cases is one that highlights the collection’s cookbooks. In 2003 the Kentucky Library was the beneficiary of a large number of cookbooks from the estate of Jeanne (Leach) Moore, a Morgantown native. This collection included over 1,500 titles that were added to the collection. This was expanded significantly with a gift from Albert Schmid a few years later. Without a doubt, Library Special Collections boasts one of Kentucky’s most significant cookbook collections. This case features the variety of cookbooks found in the collection ranging from an 1823 early-American cookbook to children’s guides to cookery. Because of the depth of this collection, cookbooks are used throughout the exhibit.

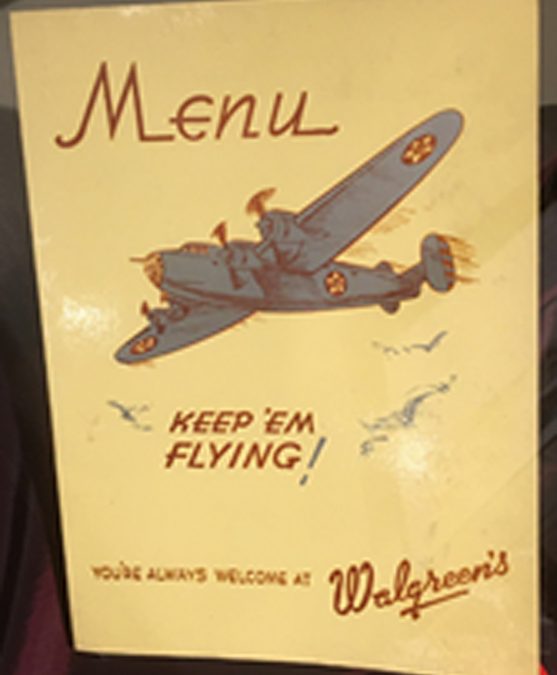

Another focal case features menus from restaurants across the state, ranging from dime store soda fountain menus to those from fine Louisville restaurants. These items are cultural treasures, as they share fares available at various food establishments, costs of items, logos and trademarks, and colorful graphics. This case also includes examples of matchbooks, once a ubiquitous give-away at restaurants, postcards, and business cards.

One case includes material related to stoves and ranges. Generally a stove uses coal or wood for a fire source, and a range uses electricity or gas. This case features cookbooks from several appliance companies, photographs of these appliances, and promotional material issued by various manufacturers. Included is a photograph of the showroom of the Louisville Tin & Stove Company which shows many of the company’s wares on display. Also included is a catalog from the same company which indicates the great array of stoves and other items produced by this concern. The last two items were donated by Pam Elrod. The highlight of this case is a miniature toy stove donated by Marjorie Claggett and appears courtesy of the Kentucky Museum.

Other cases feature images and publications from Western Kentucky University food science classes and other campus food related activities; labels and other items of food packaging; material highlighting some Kentucky food specialties such as cream candy, Hot Browns, derby pie, and mint juleps; and large posters and photographs that document certain aspects of food in the Commonwealth.