The surrender of Confederate cavalry leader John Hunt Morgan on July 26, 1863, marked the end of the “Great Raid,” his 18-day charge from Kentucky into Indiana that veered east into southern Ohio. There was “a great scare here,” reported infantryman Aaron Stuver in a letter to his sister from Cincinnati, “and we had to turn out in full strength” as the state militia scrambled to defend the area against Morgan and his raiders.

Morgan ultimately brushed past Cincinnati—“or we might have had an interview with the rebels,” wrote Stuver. Splitting up his troops, he then caused havoc as he charged through southern Ohio ahead of a major battle in Meigs County, at Buffington Island on the Ohio River. The largest Civil War engagement in Ohio, the battle memorably witnessed the death of Major Daniel McCook, one of fifteen in his family who saw service with the Union. The patriarch of the “Fighting McCooks,” as they were known, was buried in Cincinnati after a large funeral in which four companies of Stuver’s regiment participated as escorts. During the ceremonies, both enlisted men and officers, wrote Stuver, stood up to a soaking rain “like good soldiers.” McCook, he observed, “was a Paymaster in the Army, and went voluntarily after Morgan, he was 60 years old.”

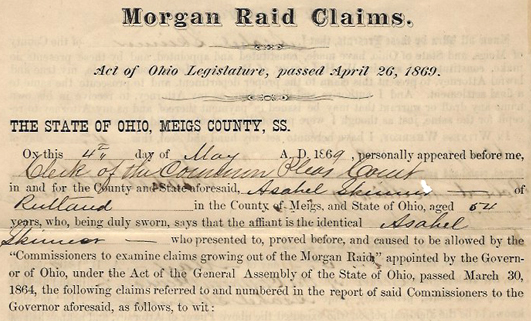

While the Great Raid accomplished little lasting good for the Confederates, it succeeded for a time in siphoning off Union forces from important offensive measures in east Tennessee. It also caused fear and uncertainty among civilians in Indiana and Ohio, many of whom suffered loss and damage to property that had been seized by Morgan or otherwise caught in the crossfire. Eight months later, the Ohio legislature created a commission to assess claims, and in April 1869 authorized the payment of compensation. The final cost Morgan extracted for the Great Raid was the printing of special forms for “Morgan Raid Claims,” on which farmers like Asahel Skinner of Meigs County certified their losses. Skinner received a total of $220 for two horses, bridles and other provisions, and for the death of a colt.

Aaron Stuver’s letter and Asahel Skinner’s damage claim from the Great Raid are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click on the links to access finding aids. For more Civil War collections, click here or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.