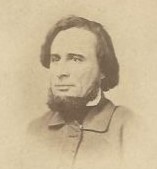

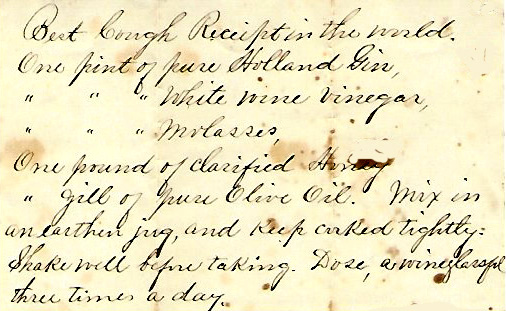

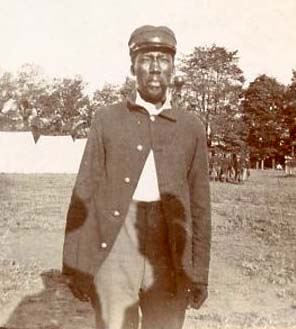

Although he had retired in 1892, Civil War veteran and Warren County, Kentucky native Captain Richard Vance took great interest in all aspects of his country’s prosecution of the Spanish-American War. Among the topics covered in his personal scrapbooks, letters and essays was the plight of American soldiers who had volunteered for the war only to be met with disease, poor camp conditions, and substandard food and medical treatment.

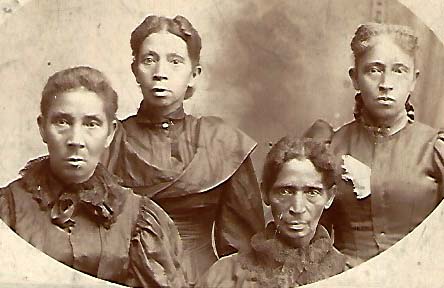

For African-American soldiers, Vance realized that the conditions were far worse. He noted that, in spite of their outstanding gallantry, African-American troops could not escape the racism of their white counterparts; in particular they “continued to be despised objects in the estimation of southern volunteers.” Vance cited an example in which “certain Virginia gentlemen (volunteers) refused to receive their pay because it was offered to them by a Negro paymaster.” He had heard stories of “disorders” in some African-American regiments, but dismissed them as no worse than those in other volunteer organizations. His own long military experience had taught him “that the ‘white-washing’ process is invariably used in such cases.”

Vance included clippings in his scrapbook to illustrate his points. During the fierce battle around Santiago, Cuba, read one report, African-American soldiers not only “fought like devils” but came to the aid of the wounded, and when wounded themselves showed “more nerve” under the surgeon’s knife “than many of their fellow soldiers of lighter hue.” When the men returned home, Louisville, Kentucky offered cheers for the 10th Cavalry—“The Colored Heroes of San Juan Hill”—but as the troop trains passed through Richmond, Texas and Meridian, Mississippi, they were targeted with gunfire. When Charles Mason Mitchell, a veteran of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, attempted to pay tribute to the bravery of his African-American comrades during a lecture in Richmond, Virginia, he was booed off the stage. “Is there a remedy for these evils?” asked Vance. “Yes. Unquestionably. Will it ever be applied? That remains to be seen.”

Click here for a finding aid to the Richard Vance Collection, and here for a gallery of primary resources in the Department of Library Special Collections relating to the Spanish-American War. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.