The only sounds: pages turning softly.

This is the quietness

of bottomland where you can hear only the young corn

growing, where a little breeze stirs the blades

and then breathes in again.I mark my place.

I listen like a farmer in the rows.“A House of Readers” from The Mountains Have Come Closer (1980)

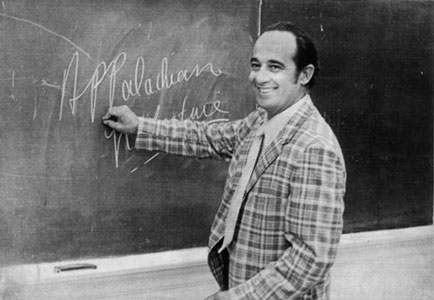

Raised on a 70-acre farm in Buncombe County, North Carolina, Jim Wayne Miller was no stranger to the secrets of the Appalachian foothills. Miller’s poetry, inspired by the works of writers such as Annette von Droste-Hulshoff, Donald Davidson, Randall Stewart, and Emil Lerperger, ultimately reflects his intimate connection to the cultural landscape of the South.

In the spring of 1982, WKU folk studies student Mary Kate Brennan interviewed Miller about “what he considers to be the central theme of his poetry, the development of his poetic art…the death of Appalachian culture, and the urgent need for the people of Appalachia to regain, or retain, pride in their cultural heritage.” Brennan’s interview, less than an hour long, is ambitious in its scope and grapples with the complex intersections between folklore, identity, language, art, and politics. In this interview, Miller also reveals his inspiration for the creation of three recurring figures throughout his poetry—the Brier, the Intellectual, and the Redneck—and how each character represents various aspects of the southern experience. In doing so, Miller addresses his turn towards “culturally aware” poetry, when he suggests that

people [in the Appalachian region] have been badgered into feeling that their society and their traditional life was in many ways inadequate, and oftentimes they’ve been only too glad to abandon traditional ways of life because they’ve been shamed out of them in various ways. But there’s a wonderful steadiness and independent mindedness that’s reasserting itself in the region.

At the time of Brennan’s interview, Miller had already been working as a full time faculty member in the Department of Modern Languages and Intercultural Studies at WKU for more than a decade, and his reputation as a distinguished professor and poet earned him several notable awards. His collaborative partnerships with the Poet in the Schools Program in Virginia, Hindman Settlement School in Kentucky, and Appalachian Studies programs in universities across the central Appalachian region served as a testament to his commitment both to public folklore endeavors and engagement within the academy.

Up until his death in 1996, Miller continued to write and publish collections of poetry, along with novels, essays, anthologies, and articles in which an undercurrent of folklore flowed freely. Speaking to the necessity of creative vernacular expression, Miller tells Brennan that “folklore is always such an integral part of peoples’ lives. You don’t go and find people sitting on the porch breaking beans and spouting one piece of proverbial wisdom after another! It’s all mixed up in life.”

Collections of Jim Wayne Miller’s poetry are available in the Helm-Cravens library stacks and in the non-circulating Special Collections stacks located in the Kentucky Building.

For more information on Jim Wayne Miller, the Appalachian region, poetry, and folklore, visit TopSCHOLAR or browse through KenCat, a searchable database featuring manuscripts, photographs, and other non-book objects housed in the Department of Library Special Collections!

Post written by WKU Folk Studies graduate

student Delainey Bowers