July 20 at 10:56 EDT marks the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s first step onto the moon. Those of a certain age will remember the blurry TV images, Armstrong’s “one small step for man” declaration, and the achievement of President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 challenge to the nation to put a man on the moon before the close of the decade.

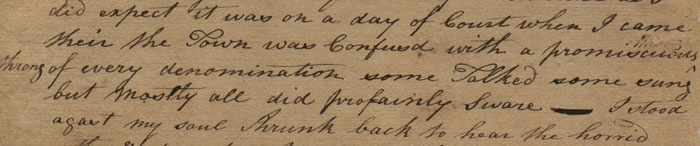

Mary (Rodes) Helm and her husband, Auburn, Kentucky native and New York banker Harold H. Helm, had been invited to Cape Kennedy to witness the launch of the Apollo 11 spacecraft on July 16. Their host, Jim “Mac” McDonnell, the founder of McDonnell Douglas, was a space-age enthusiast whose company had been involved in the mission. Mary had been initially reluctant to endure the crowds and Florida’s summer heat, but returned from the launch with a change of heart. “It was a very moving and emotional experience which I did not expect,” she wrote her father, retired Bowling Green judge John Rodes. “It may have been crowd psychology – so many thousand breathless & with a single thought & prayer. But when that rocket went up as you saw it on TV – a man behind me murmured ‘God speed,’ I felt tears rolling down my cheeks.” At a dinner the previous evening, she had met other astronauts from the program, including Wally Schirra (Apollo 7) and Jim Lovell (Apollo 8 and later 13).

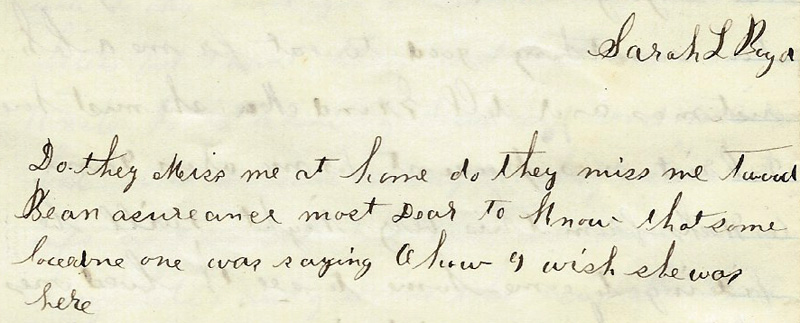

Others in Bowling Green were equally uplifted. “Wasn’t the moon landing and spectacular walk exciting?” Mary Kimbrough declared to a friend. But like Mac McDonnell, who quickly asked “What next?” after the success of Apollo 11, she was looking ahead. “They announced that my cousin, Jack (Harrison) Schmitt will go on the next trip – Apollo 12,” she wrote (he actually flew on Apollo 17). “We’ve always said ‘Man in the Moon.’ We have to revise that to say ‘Man ON the Moon.’”

One of the unknowns about Apollo 11 was the danger of invasion by alien microbes or “moon bugs,” a possibility that kept the astronauts in quarantine for more than two weeks after their return. But three years later, it was the cargo of rocks brought back from the lunar surface that scientists sought to keep in pristine condition. In August 1972, a loan of one of these moon rocks arrived for display at WKU’s Hardin Planetarium. To protect against leakage and contamination by the earth’s atmosphere, the sample was sealed in a container filled with pure nitrogen. More than four billion years old, it was part of a 70-pound haul collected during the Apollo 11 mission.

Click on the links to access more information about these materials, housed in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections.