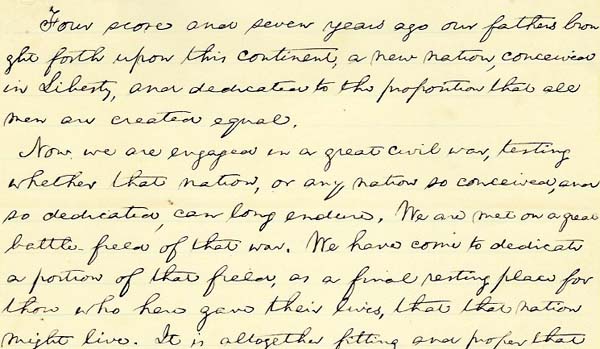

When, in 1953, she decided to do her doctoral dissertation on Kentucky author Jesse Stuart, West Virginia native Mary (Washington) Clarke could have asked for no better cheerleader than Stuart himself. “You are the first ever to select my work for a dissertation and you will get the fullest cooperation I can give you,” wrote Stuart, the “voice of the Kentucky hill country,” whose prolific output of novels, short stories, poems and non-fiction would make him one of the 20th century’s best known regional writers.

Clarke’s dissertation, which she adapted into a 1968 book, Jesse Stuart’s Kentucky, marked the beginning of a friendship with Stuart that lasted until his death in 1984. By the time the book was completed, Clarke and her husband Ken had joined the faculty of WKU, where they would become recognized authorities on Kentucky folklore. Stuart celebrated with Clarke when Jesse Stuart’s Kentucky was published and joined her at book-signing events. His letters to Clarke kept her abreast of his writing projects and speaking engagements and gave her support and encouragement in her other scholarly endeavors. He commiserated with Clarke on accommodating the demands of publishers and picky manuscript readers, and was curious about the jealousies and anti-academic prejudice that sometimes dogged a successful scholarly author. His support continued during Clarke’s work on Jesse Stuart: Essays on His Work, a 5-year-long effort that saw Clarke and her co-editor coaxing contributions from busy academics and critics, then crafting the results into a volume worthy of publication.

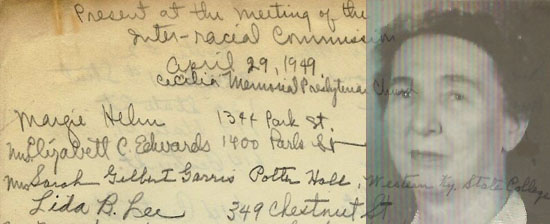

Mary (Washington) Clarke’s papers, which include her correspondence with Jesse Stuart and other materials on her scholarly work, are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more on Mary, her husband Kenneth, and Jesse Stuart, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.