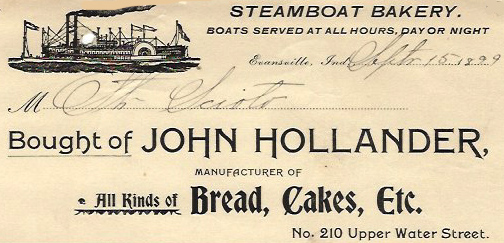

Thanks to lock and dam construction by the Rough River Navigation Company, incorporated in 1856, the citizens of Hartford and Ohio County, Kentucky once enjoyed regular steamboat traffic along that tributary of the Green River. Late in the 19th century the Scioto, a 94-foot-long craft owned by the Hartford and Evansville Packet Company, transported both freight and passengers between Hartford and Evansville, Indiana.

The daily demands of operating the Scioto are documented in a collection of bills and receipts held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Dated 1899, they show the expenses necessary to maintain this floating conveyance of people and goods. We see purchases of foodstuffs such as flour, peas, corn, butter, coffee, ketchup, sugar and potatoes; provisions such as oil, matches and deck brooms; services rendered for laundering sheets, towels and tablecloths; and repairs to stoves, pipes and flanges. The Scioto‘s crew did business at both ends of its route, so Hartford and Evansville merchants are well represented. Some of these firms catered specifically to the steamboat trade, promising to serve their customers’ needs “at all hours.” Many of the Evansville businesses were appropriately located on Upper Water Street, now Riverside Drive.

Click here to access a finding aid for the Scioto steamboat collection of receipts, and here to learn about our premier collection of Ohio River Valley steamboat photographs. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

Click here to access a finding aid for the Scioto steamboat collection of receipts, and here to learn about our premier collection of Ohio River Valley steamboat photographs. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.