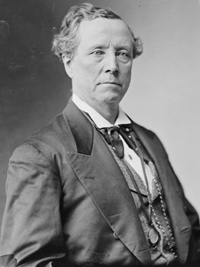

This week in 1804 saw one of the most famous duels in American history when, on July 11, Vice President Aaron Burr faced down his bitter rival, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, who died the next day of his wounds, had offended Burr’s honor by attacking him relentlessly during his attempts to secure renomination to the vice presidency and then to win the governorship of New York.

One of Kentucky’s most famous duels occurred on February 3, 1801 between John Rowan, the rising lawyer and politician of “Federal Hill” fame, and Dr. James Chambers. Both men were prominent citizens, but their affair of honor began with a rather seedy encounter in a Bardstown tavern. Chambers was irritated that night over his losses at cards, and Rowan, by his own admission, had had too much to drink. They first argued over the card game; then Rowan, who had excelled in the classics as a student, disputed Chambers’s claim to possess greater proficiency in the “dead languages.” This was enough for Chambers to issue a challenge, coupled with the threat that if Rowan did not accept, “he would publish him as a coward in every paper in the State.”

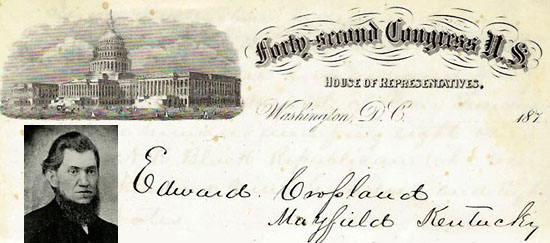

On the day of the duel, the men faced each other in the woods outside Bardstown. Each took careful aim at the other, but missed. A second round ensued, and Rowan wounded Chambers in the chest. Then, as Frances Richards notes in her biography of Rowan, “the peculiar code of duelling” kicked in. Rowan gallantly offered to summon his carriage to take Chambers back to town. When Chambers died the next day and Rowan was arrested, even some of Rowan’s fiercest enemies “objected to having a man whose difficulties had been settled according to the ‘code,’ punished by law.” In a letter to his brother-in-law, Rowan claimed that the dying Chambers himself had “begged his friends not to prosecute me.” Commonweath Attorney Felix Grundy reportedly resigned rather than bring his boyhood friend to trial. Ultimately, the charges against Rowan were dropped. He went on to become Kentucky’s Secretary of State, a member of Congress, a state legislator, and a judge on the Court of Appeals.

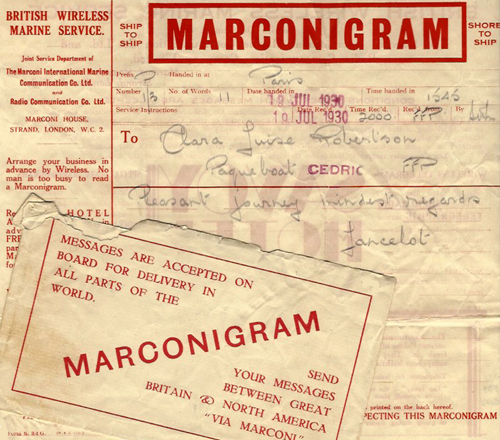

Click on the links to access finding aids for collections relating to the Rowan-Chambers duel, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For more collections relating to duels, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.