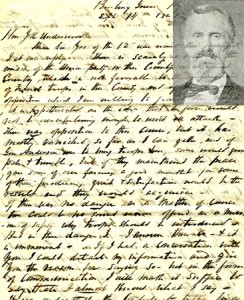

Bowling Green native Elizabeth Robertson Coombs (1893-1988) spent much of her youth in New York City, but returned to Kentucky after the early death of her father, a railroad executive. When the U.S. entered World War II, Coombs, who had worked for a decade as a reference librarian at WKU’s Special Collections Library, was ready to volunteer her skills. In 1942, she filled out an application to serve with the local branch of the Red Cross Motor Corps. She noted her proficiency in French, gave WKU uber-librarian Margie Helm as a reference, and for some reason boldly lopped nine years off her date of birth.

The Motor Corps was no delicate feminine pastime. In their dark grey uniforms and caps, and with an identifying metal disk attached to their licence plates, volunteers undertook a variety of tasks related to the civilian war effort: carrying messages and deliveries, ferrying public health officials to their duties and children to hospital in Louisville, driving mobile canteens, transporting supplies for the blood donor program, doing office work and assisting at public gatherings. Members attended meetings at the Bowling Green Armory and were liable to be discharged if they missed more than three; an acceptable excuse, however, was having a husband home on furlough.

In order to qualify for the Motor Corps, Coombs completed Red Cross first aid training, then took a 30-hour course in motor mechanics where she learned to change tires, put on chains, adjust brakes, and replace spark plugs. But the Motor Corps also provided support to the civil defense authorities, and consequently Coombs received additional education in war’s worst-case scenarios, including the possibility of chemical attack. She learned about the telltale odor of tear gas (fly paper or apple blossoms), mustard gas (horseradish), and paralyzing gases (bitter almonds or rotten eggs), the symptoms of exposure, and what aid to administer.

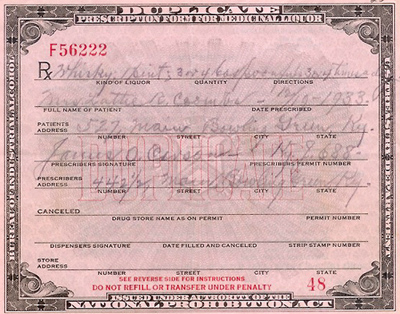

Fortunately, for Coombs and her fellow citizens, the discomforts of the home front did not extend beyond coping with a scarcity of consumer goods and a federal system of rationing and price controls. Instructions on her books of ration stamps for food and gasoline gave her the right “to buy your fair share of certain goods” at reasonable prices. “Don’t pay more” on the black market, warned the Office of Price Administration–and, conversely, “If you don’t need it, DON’T BUY IT.” Some commodities required special clearance; completion of a two-page form allowed Coombs and her mother to apply for a “home canning sugar allowance” subject to an annual limit of 20 lbs. per person and a warning to “only apply for as much sugar as you are sure you will need.”

Material relating to Elizabeth Robertson Coombs’ life during wartime is part of the Coombs Family Collection housed in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives section of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to download a finding aid. For more collections relating to the home front during World War II, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.