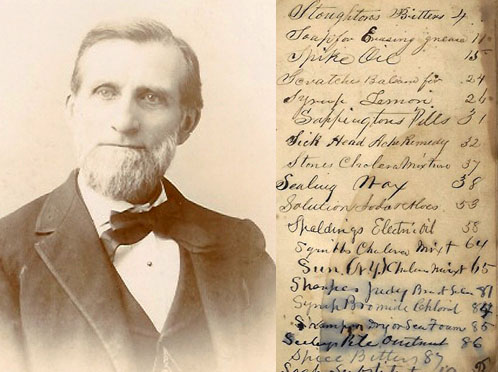

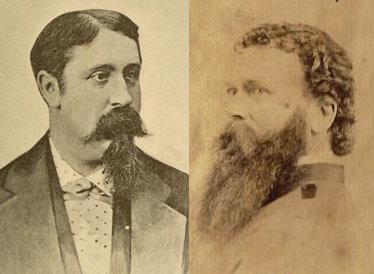

She was, by his description, a “little mulatto girl” he first encountered in 1867 during his military duty at Little Rock, Arkansas. Their ensuing 22-year relationship was neither simple nor ordinary, but the story of Sophia and Captain Richard Vance, a native of Warren County, Kentucky, is preserved in Vance’s diaries, now part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. The only thing missing from the story, sadly, is the voice of Sophia herself.

Separated from her family and cast adrift after her emancipation from slavery, Sophia, no more than sixteen years old, seemed doomed to become the sexual plaything of the officers in Vance’s garrison. Indeed, that may have been how Vance himself, who frequented local prostitutes to satisfy his need for a woman’s “delicious embraces,” initially regarded her. But he soon found himself “desperately stuck on my little girl”– my “new flame”– and when Sophia’s principal patron abandoned her, she became his servant and mistress.

Though completely smitten, Vance was fearful that his “dangerous experiment” would be discovered. Nevertheless, neither he nor Sophia were inclined to end the relationship, and he was relieved in 1869 when he managed to bring her along to his new posting at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In 1876, they were at Fort Dodge, Kansas, where Sophia married and departed, Vance assumed, for a new life. Before long, however, both Sophia and her husband George returned and took up the care of his household. Throughout Vance’s subsequent duty in the Indian Territory, Colorado and Texas, they turned his military lodgings into a comfortable home, anchored his life, and eased his restlessness and unhappiness with the Army. When Henry, a young boy abandoned to Sophia’s care, joined the household, an odd but strangely durable family unit was created.

Everything changed late in 1888, when Vance returned to Fort Clark, Texas from a lengthy trip to find Sophia ill. He had been wearily searching for a place to retire and had even purchased a farm near Washington, D.C., but was torn between bringing Sophia, George and Henry into his post-Army life or making a clean break. Only after watching in anguish as Sophia sank and died in May 1889 did he understand what he had lost. His diary entry cried out simply: I am in a world of trouble. Sophia.

Wandering from place to place in retirement, Vance routinely turned his thoughts back to his years with Sophia. “Those were my best and happiest days,” he wrote, “the like of which I must not expect to see again, for there was but one Sophia.” On a January morning in 1893, he found the scene outside his lodgings so reminiscent of “the prospect from the back window of the last quarters I occupied in Ft. Clark that I can easily fancy that I have but to go below to find Sophia busying about some household duty; to find Henry playing with his toys in the yard; to find the dogs lazily dozing in the wood shed; and all the paraphernalia of my old establishment.” For Vance, who never married, Sophia represented a golden age that he had failed to appreciate and to which he could never return.

Click here for a finding aid to the Richard Vance Collection. For more collections search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.