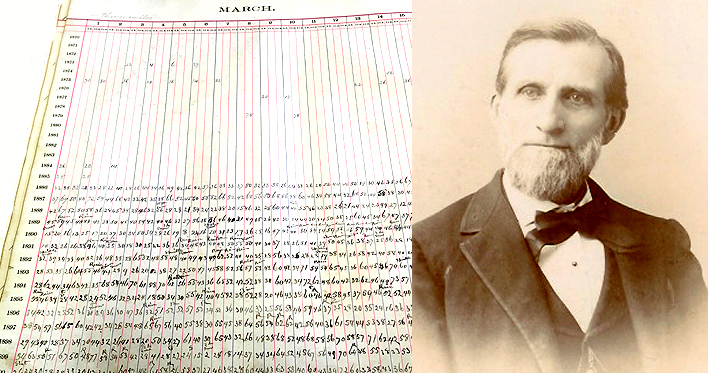

In 1896, Owen County, Kentucky native Robert Gentry struck out on his own. At only 31, he founded the Bank of Sonora in Hardin County and, as it turned out, would remain associated with the bank for more than 50 years.

In 1905, however, Gentry, his wife Mattie and two young sons were thinking about striking out again, this time for the West.

Beset by illness, the couple considered California as a place where Robert could resume banking or some other business, and both could recover their health. Seeking information from friends and acquaintances who were familiar with the region, Robert received some enthusiastic responses about the potential of the Golden State. One boasted of “over a million dollars of building” in Los Angeles in July 1904 alone. Eager for a new investor, another friend touted the success of his Los Angeles printing business. The city’s future was assured, he noted, by the approval of an ambitious (but controversial) aqueduct system to supply water from the Owens River in the east.

But what could Robert’s wife Mattie expect? Suffering from a lung complaint, possibly tuberculosis, she seemed prepared to make the move first and leave her husband to tie up matters at home. Accordingly, she would have carefully read a letter from Corinne Phillips, the Kentucky-born niece of a family friend and a resident of Tustin in Orange County, that provided some additional perspective on life in southern California.

In simple matters of heat and humidity, Corinne advised, there were many choices. Though it was the “garden spot” of Orange County, Tustin could be a little too damp for those with weak lungs. The town of Orange offered a drier climate, as did communities like Riverside, Redlands and San Bernardino. Even drier—“on the verge of the desert”—were Palm Springs, Beaumont and Hesperia. Pasadena, with its healthy climate, was called the “Second Paradise.”

But Corinne knew that other aspects of her new home would be important to Mattie. The desert towns, she warned, “are rather lonely places” for an unaccompanied woman, and Westerners in general, though possessed of some good qualities, were not as sociable as Kentuckians. “I speak of the southern people,” she wrote, “because I know the South is dear to your heart.” Santa Ana, for example, “has quite a number of southern people in it,” but Mattie should keep in mind that “every man is “rustling for the ‘Almighty Dollar’ and he takes it for granted that you are doing likewise.” In a region where “everything is business” she would have to shed any tendency to “be dependent on the stronger sex.” Women were “placed on an equal footing with men,” Corinne observed, “and you are supposed to rustle for yourself.”

Overall, Corinne advised, Mattie should come prepared to be flexible and “to make the best of things.” She should bring a letter of introduction from her pastor, “for it will open to you an avenue of friends.” She might “see and hear things that would shock your modesty, but don’t worry over it let it go. For everything goes out west.” Boarding house rates varied – from two to six dollars per week – but if she committed to a stay of six months to a year, Corinne declared, Mattie would never want to leave. “You will send for your husband and children [and] build for yourself a house in sunny, southern California.”

Corinne Phillips’s letter to Mattie Gentry is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.