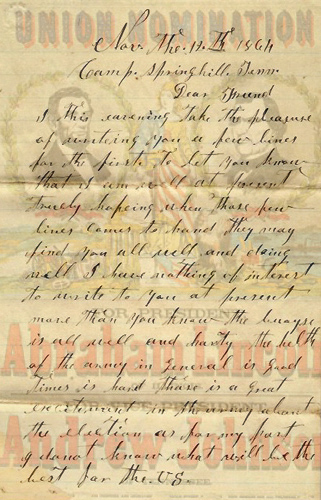

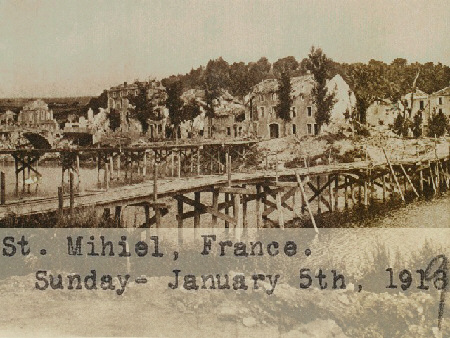

Like many of us at this time of year, he had to correct his typed letter by hand to change “January 5, 1918” to “1919.” Mt. Olivet, Kentucky’s Howard Buckner had just moved to quarters on the outskirts of St. Mihiel, France, joining a long line of soldiers awaiting demobilization and return home following the end of World War I.

Buckner and his detachment of 36 men and 3 officers found St. Mihiel inching toward recovery after four years of war. About the size of Maysville in Buckner’s estimation, it had, he learned, been considered a “very fine place.” But then came the occupying Germans, and repeated efforts by the French and British to retake the town. Finally, the Americans had come along and recaptured it “in six hours,” according to Buckner. The Yanks’ secret was their willingness to shell the town into submission, but Buckner insisted that far more damage had been done by the retreating Germans, and French families had continued to reside there throughout the war.

Nevertheless, Buckner and his men faced the immediate task of creating decent living quarters for themselves in the middle of the devastation. Most of the “desirable ‘ruins,’” he explained, had already been taken, and “we got the ‘left-overs,’” which required the men to brush off their handyman skills. But they had fixed up two houses, “with a stove in every room” and everything “nice and dry.” Some of his men joked that “if their wife is cross and fussy with them upon their return home” they would be well accustomed to taking a blanket and curling up on the porch or in the woodshed. They had yet to explore the town itself, but Buckner had heard rumors of normalcy: “lots of little stores, hotels and everything that goes to make up a real city.” Rations were plenty, local delicacies were available to buy, and there was a YMCA with the possibility of “entertainment on tonight.” Things were clearly looking brighter.

Buckner’s thoughts, however, were on home. Rainy winter weather was setting in—the swelling River Meuse, he observed, resembled “the Ohio river during the 1913 flood”—and the men stood ready to depart “as soon as there’s a boat to carry us.” Buckner declared to his family that he was determined to “be with you all again” and “do everything within my power to interest you and make things more pleasant.” For now, he trusted that they would encounter “only the richest blessings” in the New Year.

Howard Buckner’s letter is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid and scan. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.