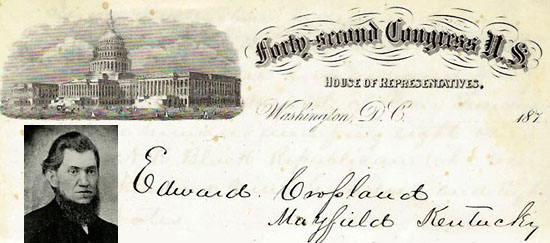

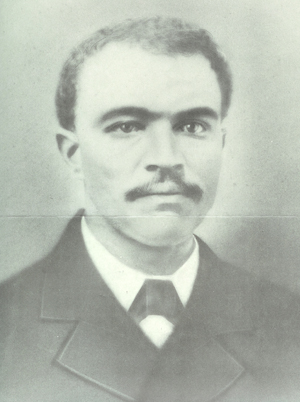

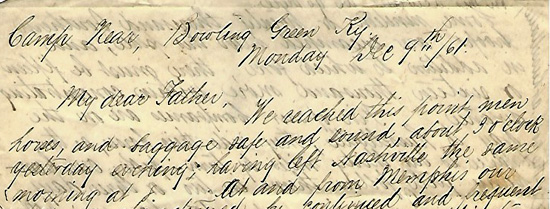

It was an impressive resume, probably written for the Congressional Directory, that Edward Crossland (1827-1881) composed on letterhead of the 42nd Congress of the United States. Elected as a Democrat in 1870 to represent Kentucky’s First Congressional District, the Hickman County native was a lawyer and former state representative who had resigned a judgeship in order to go to Washington. Among his accomplishments, Crossland carefully noted the margin of his electoral victory–7,930 votes to 2,980–over his GOP opponent.

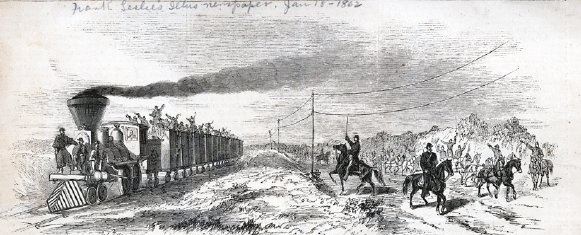

As is common in a mid-term election, President Ulysses S. Grant’s Republican Party had lost seats in the House, but retained its overall majority. Also expected, perhaps, was Crossland’s omission, in these first years of Reconstruction, of some dramatic biographical details: as an officer in the Confederate Army, he had seen battle in Virginia, Mississippi and Alabama, the last being under controversial Lieutenant-General Nathan Bedford Forrest (“that devil Forrest,” in U.S. Grant’s words) as he tried to defend Selma in the last days of the Civil War.

Crossland’s non-disclosure of his military career might have led to a flurry of cable news comment today, but there was no cause for concern among his supporters in the South, where Democratic candidates successfully ran against Radical Republicans and their civil rights agenda. On March 11, 1871, in fact, the Hickman Courier expressed relief at the news that Crossland had been duly sworn in as a member of Congress. “Many leading men in this District,” the editors reported, “entertained serious apprehensions that Radical vindictiveness would seek to exclude him from the seat to which our people had elected him.”

Edward Crossland’s handwritten biography is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For other Kentucky political collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.