When Union troops arrived in Bowling Green, Kentucky in February, 1862 after a 5-month-long Confederate occupation, they found a town stripped of its timber, livestock and foodstuffs, its railroad depot set afire, its Barren River bridges destroyed, its secessionist sympathizers in flight, and its Northern sympathizers relieved but still apprehensive at the sight of another occupying force.

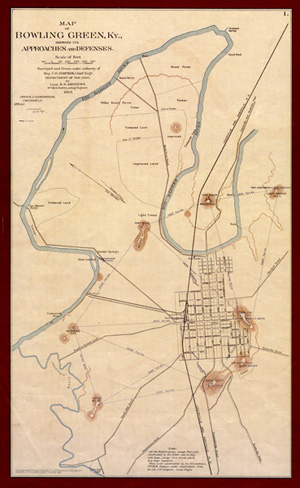

Despite the destruction, the troops also found a daunting array of Confederate fortifications. Bowling Green, at the confluence of road, rail and river routes into the South, was considered a prize by both sides, and the defenses constructed during their occupation had emboldened the Confederates. We “are too well fixed for the Yankees to come here,” Tennessee volunteer James McWhirter boasted to his sister. “If they ever come we will give them a genteel whipping.”

The Confederates, nevertheless, had evacuated without a major clash ever taking place, a stroke of luck that left the Union forces relieved. “I don’t think it would pay them to attack this place from the looks of the forts around here,” Erasmus Shull wrote his aunt. Lieutenant Colonel George Jouett was similarly impressed, calling Bowling Green a “city of fortifications.” The College Hill fort was “an almost unapproachable fortress,” he wrote his mother, and Baker Hill is “quite as strong and perfect.” Ohio infantryman George Jarvis notified his family of “a glorious but bloodless victory” that “gives us possession of one of the strongholds of this state.”

Accounts of the war came to describe fortified Bowling Green as the “Gibraltar of Kentucky.” Two of the above letters, however, confirm that this was a contemporary characterization. George Jouett found Bowling Green a “Gibraltar which could not be taken by assault,” and George Jarvis agreed that “in fact it is the Gibraltar of Kentucky.” Only lack of supplies, illness, and setbacks elsewhere (losses at Mill Springs and Fort Henry, and pressure at Fort Donelson) had convinced the Confederates to withdraw before a serious test of its defenses.

These letters about Bowling Green’s Civil War fortifications are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click on the links to access finding aids, and click here to browse a list of our Civil War collections. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.