Frank Phelps letter, 1862

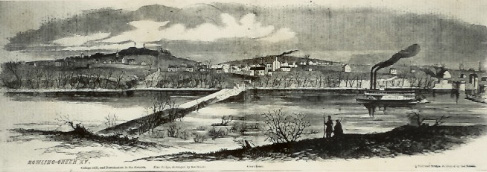

The Civil War came to Bowling Green in mid-September, 1861, with the arrival of General Simon Bolivar Buckner and about 1,300 Confederate soldiers. They were soon joined by more than 20,000 troops who set up camp in and around the town. From their fortified positions on surrounding hilltops, the Confederates looked forward to giving, in one soldier’s words, a “genteel whipping” to any Union forces foolish enough to confront them. As winter set in, however, rainy conditions, poor food and shelter, inadequate clothing and rampant disease wore down the troops.

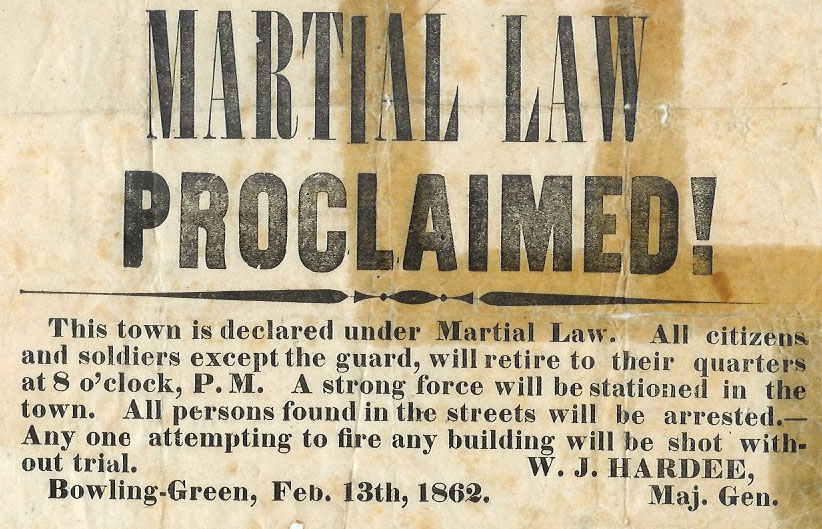

In mid-February 1862, facing the advance of a large Union force into the area, the Confederates decided to abandon Bowling Green. Frank M. Phelps of the 10th Wisconsin Infantry was one of the soldiers who helped reclaim the area for the Federals. Writing a long letter to his uncle back home, he reported crossing the Green River and camping at Munfordville before heading for Bowling Green. During the brisk march, a “long cheer” erupted from the troops when word came that advance units were shelling the little town. Phelps and his comrades encountered ponds that the Confederates had fouled with the carcasses of dead horses in order to deny fresh water to the enemy. Once in Bowling Green, Phelps remarked on the extent of the fortifications, the destruction of the railroad depot, and the general disarray caused by the Confederates’ unceremonious departure. The secessionists had “called their troops & run as fast as they could,” he wrote, “after setting fire to about 100 tins of salt pork. [T]he streets are full of sugar salt beef & pork flour & every thing else.” In a postscript, Phelps reported the capture of a “sesesh Captain” who had lingered behind and wore a disguise in hopes of evading detection.

This fascinating letter is now a part of WKU’s Special Collections Library manuscripts collections. A finding aid and typescript can be downloaded here.

For more on our extensive Civil War resources, click here.