It was originally called Decoration Day, a time to place flowers on the graves of the war dead. Now, as Memorial Day, it also marks a long weekend, store sales, and the beginning of summer, and the public is often indifferent to the solemnity of the occasion.

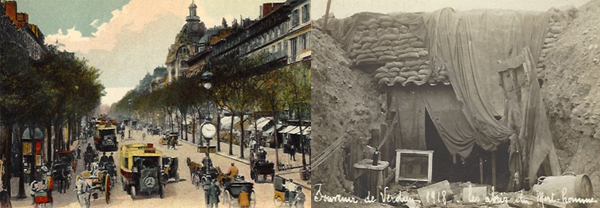

For James Knox Polk Lambert, its meaning was fresh. In Paris on May 30, 1919–Decoration Day–the Kentucky native was on duty with the YMCA, ministering to soldiers awaiting repatriation after World War I. “Delightful weather,” he observed in his diary, “and charming scenes–bright sunshine, a clear sky, soft atmosphere, rich blooming flowers, sweet singing birds and throngs of well dressed people from all parts of the world.”

But the contrast between that lovely spring day, and the past year spent touring a country shattered by war, immediately clouded his thoughts. Wrenched back to all that he had seen during his time overseas, he continued:

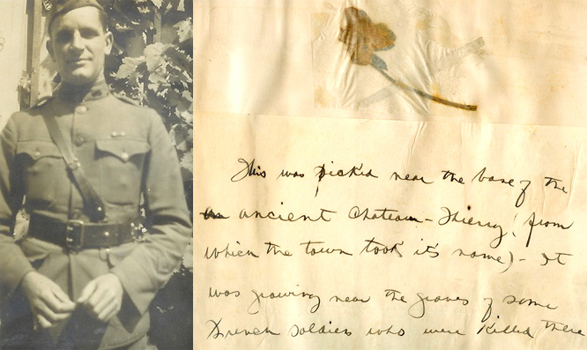

It is not possible to decorate with flowers all the graves of this war’s dead. They are too many, too widely scattered; in France, Belgium, Italy; in the Balkans, the Gallipoli peninsula, Mesopotamia; in Russia and the Far East; in unmarked graves and in the fathomless ocean, but wherever they are, sleeping in great cemeteries or still in lonely graves hard by their rendezvous with death, they are not forgotten.

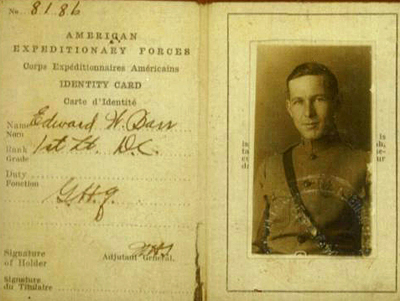

James Lambert’s diary is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For other war collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.