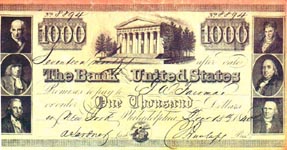

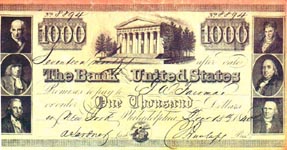

A $1000 note – or is it $100?

In spring 1827, John Boon took four flatboats of tobacco to New Orleans and made a killing. His earnings of more than $6000 included two $1000 bills drawn on the Bank of the United States. On the way home to Logan County, Kentucky, Boon instructed an agent to make a payment to Urban E. Johns, a member of the religious society of Shakers at South Union, for another boat that Johns had agreed to build for Boon at a cost of $110. Unfortunately, the agent didn’t notice the extra zero on the bill, and paid Johns $1000 instead of the $100 intended. A year and a half later, Boon discovered the error and sued the Shakers to get his $900 overpayment returned.

The claim was fabricated, answered nine representative Shakers on whom it had been served. They lived and worked together for their economic as well as spiritual benefit, they explained, and the arrival of a $1000 windfall, dishonestly retained by a member, would have spread through the society like wildfire. The con, they alleged, had been recently suggested to Boon by a disgruntled ex-Shaker. Hoping that the society, already sensitive to public suspicion of its creed, would simply pay up to avoid bad publicity, he “hungrily caught at the bait.”

Boon misjudged the Shakers, who not only beat him in court but received judgment against Boon for their costs. Along the way, the Shakers took particular exception to a state law passed in 1828 that allowed anyone with a money claim against them in excess of $50 to sue in chancery court in the absence of a jury. Finding themselves singled out “as the peculiar object of legislative severity,” the Shakers protested bitterly that their constitutional protections had been unjustly diminished on account of their religion.

The documents relating to John Boon v. Society of Shakers at South Union are part of the Billy Holman Collection at WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to download a finding aid. For more on the Shakers, search TopScholar and KenCat.