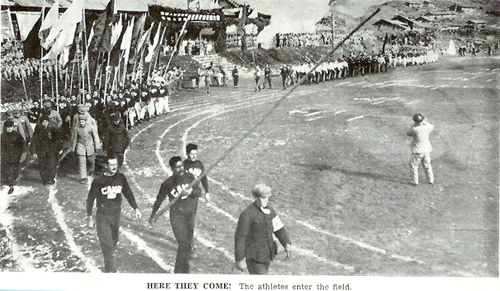

On November 15, 1952, three months after the summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, another Olympic-style opening ceremony began on the other side of the world. Some 500 athletes entered a field carrying “brightly colored banners adorned with the symbolic peace dove.” An official lit a torch, then the athletes took an oath and filed off the field to the tune of the “March of Friendship.” Over the next 11 days, they competed in track and field, volleyball, wrestling, soccer, football, basketball and boxing. They enjoyed food, fun and high spirits, even nightly entertainments featuring songs and sketches.

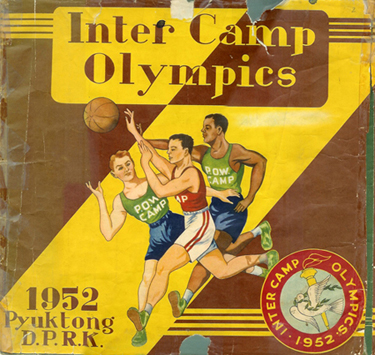

That was the official version. But these games were a sham, for the location was Pyuktong, North Korea, during the Korean War. The “athletes” were prisoners-of-war drawn from every camp in the country, pawns in a propaganda exercise intended to portray the North Koreans in a positive light and emphasize the hospitality they lavished on their captives.

The activities of the “Inter Camp Olympics” were summarized in a souvenir booklet produced by and for the prisoners. In bizarrely effusive language, contributors described their experiences. “It was the most colorful and gala event to come about during our stay here in Korea under the guidance of our captors,” gushed Clarence B. Covington. “I am certain that no one in his sane mind will ever say that prisoners of war over here are not the best cared for in the whole world today.” George R. Atkins agreed. “At all times the cooperation, generosity, enthusiasm, and selfless energy displayed by our captors was perfect . . . . The lenient treatment policy has long ago passed its title of lenient, it has instead become a brotherly love treatment.” One can only wonder which of three voices is speaking: that of the brainwashed prisoner, psychologically conquered by his tormentors; the pragmatic collaborator, dutifully repeating what his captors want to hear; or the wise guy, laying it on thick and knowing that nobody back home would be fooled by such a charade.

In 1953, while serving in Korea with the 1st Marine Corps Division, Major Belmont Forsythe, a native of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, was appointed to a United Nations team receiving prisoners of war returning from North Korea. One of them gave him a copy of the souvenir booklet for the Pyuktong Olympics, and this fascinating propaganda piece is now part of the Belmont Forsythe Collection in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives section of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to access a finding aid. For other collections relating to the Korean War and to prisoners-of-war, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.