Hannah Hudson, the youngest daughter of Mark and Scarlett Hudson, has been named the Dr. Delroy & Patricia Hire Special Collections Intern for 2019.

Hannah is a lifelong resident of Macon County, Tennessee, and a 2018 graduate of Red Boiling Springs High School. She is currently a sophomore at WKU pursuing a degree in Cultural Anthropology with a minor in Folk Studies.

The Dr. Delroy & Patricia Hire Internship was established in 2015 to provide students with professional experience working in a special collections library, specifically with material from Allen and Monroe counties in Kentucky and Macon County in Tennessee. Hudson is the fourth Hire Intern to date.

Hudson states that growing up listening to stories and folktales about the history of Red Boiling Springs led her to pursue a career in anthropology and folk studies. From a young age, she enjoyed studying the history and folklife of different cultures and was especially interested in stories from the southeastern United States. Studying cultural anthropology and folklore at WKU seemed like the perfect fit for her interests.

“I hope to pursue a career in applied anthropology, doing museum and archival research, because I find it important to preserve diverse cultures and sub-cultures,” said Hudson. “I am grateful for this opportunity to intern with the Special Collections Library and be a part of the preservation of my county and the surrounding Kentucky counties that have shaped my life.”

Dr. Delroy Hire, the son of Osby Lee Hire and Lillian K. Garrison, was born and raised in Monroe County. He graduated from Tompkinsville High School in 1959. Dr. Hire is a 1962 WKU graduate and a graduate of the University of Louisville School of Medicine. He is board certified in anatomic, clinical and forensic pathology. After furthering his education, Dr. Hire went on duty as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy and served for more than 20 years. He retired as the Deputy Armed Forces Medical Examiner based out of Washington, D.C., and now lives in Pensacola, Fla.

“In the Department of Library Special Collections, we have unique collections that allow students to literally touch history,” said Jonathan Jeffrey, Department Head for the unit. “This is more than a magnanimous gesture from Dr. Hire, it is an investment both in our collections and future curators of similar collections. Hannah Hudson is a fine example of Dr. Hire’s investment, and we are thrilled to offer her and other WKU students this opportunity.”

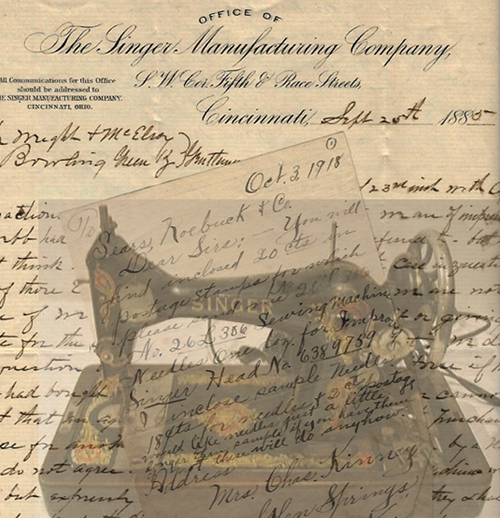

Hudson will work with a number of items related to the three counties in which Dr. Hire is interested. She will scan and log photographs from the Tim Lee Carter collection to aid in the curation of an exhibit honoring the Congressman for Monroe County’s Bicentennial. In addition, Hudson will transcribe the 1850 slave census from Monroe County and Allen County, and write a historical summary for Macon County with an annotated bibliography. The slave census data and the Macon County paper will be accessible on TOPScholar, WKU’s digital repository (digitalcommons.wku.edu)