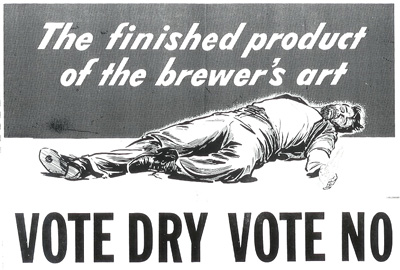

On May 9, 1960 a group of concerned citizens and clergymen, both white and African-American, organized the Warren County Anti-Liquor Association. Their aim was to fight efforts to legalize the sale of alcohol in Bowling Green, thereby preserving the outcome of a 1957 local option election in which both the city and county had gone “dry.”

In their intense campaign to influence the vote in the upcoming September election, the Association clashed not only with pro-legalization forces (“wets”) but with the Park City Daily News over publicity tactics. The Association submitted an ad to the Daily News announcing its intention to print the names of citizens who had signed petitions calling for the new vote, but the paper refused to publish it. While the petitions themselves were public records, the editors argued, the Association’s action constituted intimidation and would expose the paper to lawsuits for invasion of privacy.

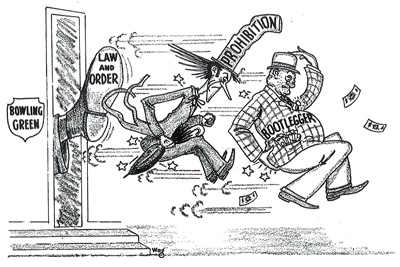

Unbowed, the Association heaped disdain on the attempts of its opponents to drape themselves in the mantle of “law and order.” Both factions despised bootleggers, “whiskey houses” and other manifestations of the illegal liquor trade, but the “wets,” who called themselves the Citizens Committee for Law and Order, favored undermining criminal profits by regulating and taxing legal sales, while the “drys” insisted on enforcement of current laws to keep all sales illegal. The rhetoric became heated as the Association accused the Citizens Committee of “fraud and deception” and even called for the indictment of its members. “Don’t be Hoodwinked,” warned its ads, predicting runaway corruption and immorality if Bowling Green went “legal.”

The election of September 24, however, saw the “wets” prevail by a 2,750-vote margin, decisively ending Bowling Green’s last experiment with prohibition. “We threw everything we had at them,” a “dry” spokesman told the Daily News the next day, “but it was not enough.”

Minutes, correspondence and other records of the Warren County Anti-Liquor Association and the 1960 local option election are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives section of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to access a finding aid. For other collections on prohibition and temperance, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.