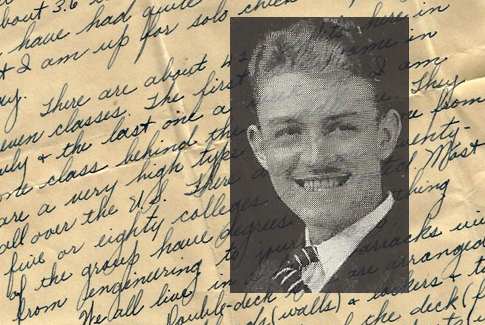

As a U.S. Army Special Services Officer during World War II, Warren County, Kentucky’s Harry L. Jackson (1907-1985) saw combat up close. Landing at Utah Beach five days after D-Day, he and his men pushed toward Germany via France, Holland and Belgium. Jackson’s duties included arranging recreation for the troops, writing a regimental history, distributing ballots for the 1944 presidential election, and preparing applications for decorations. Before long, however, he found himself doing much more: burying war dead, helping to manage waves of refugees, and juggling pleas for favors from desperate civilians. He experienced the far-away look in the eyes of exhausted combat soldiers, and the utter destruction that war brought to once-beautiful cities and villages across Europe. He also learned to cope with his own emotional tailspin after witnessing a vast panorama of human suffering that included a visit to the Buchenwald concentration camp in summer 1945.

So it was with much authority that Jackson reflected on the bitter fruits of war in an October 9, 1944 letter to his sister Juanita:

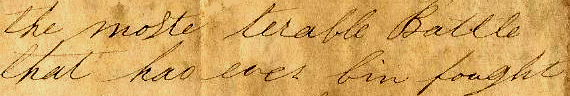

While I write this there is a terrible battle raging. . . you will never know (thank God) the terror of war – all evening long I have been listening to the artillery fire – the concussion of which shakes the building to its foundations – then there are the mortars and machine guns – then the tanks. . . the planes are over most every night. . . then to-morrow the casualty lists. . . .

I went out today – all of the houses are torn to bits – everything blown from the inside with large holes blown through the walls – all the inside contents spilling out like the bowels of a butchered pig – there are no windows – just large gaping holes in the walls through which the wind and weather plays jauntily with the lace curtains – curtains hung by some proud hand to make a home. . . makes one feel ashamed to look into the intimate privacy of these houses as they stand stripped of their raiments and stand naked before you. The people – the people that once called them home have been driven, helpless away . . . to make way for the mighty god of war and destruction. . . . .

No there is nothing romantic about it. Beauty and the lightness of life is gone. . . . but we are winning – and there will be a to-morrow of a better world I hope whether I am here to see it or not. . . . My eyes have seen too much – and my mind is filled with revolt at the scene – but I must go on – for them that have gone and for those that are out there to-night and for you at home.

Harry Jackson’s letters are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. A finding aid can be downloaded here. To browse our World War II collections, search TopSCHOLAR and Ken Cat.