My name is Hannah Hudson, and this fall, I have had the privilege of being the fourth Dr. Delroy and Patricia Hire intern in the Department of Library Special Collections. I am a sophomore at WKU, majoring in Cultural Anthropology and minoring in Folk Studies. I have always enjoyed learning about local history and the importance of rural communities in the development of the southeastern United States. When the head of my department mentioned this internship to me, I knew it would be the perfect opportunity to develop my professional skills. Throughout my time as an intern in Special Collections, I have worked on projects from Monroe County, Kentucky, Allen County, Kentucky and Macon County, Tennessee.

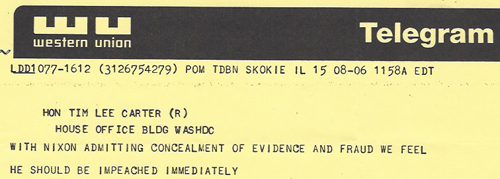

One project I have worked on this semester involves sorting, scanning, and categorizing photographs from the Tim Lee Carter Collection. Dr. Tim Lee Carter was from Monroe County, Kentucky, and he served eight terms (1965-1981) as a U.S. Representative for Kentucky’s Fifth Congressional District. Due to my interest in visual anthropology, it has been very interesting for me to see how Carter’s work as a public servant was documented through these photos. I also gained practical experience while working with this collection as I learned about the process of cataloging in Past Perfect, a widely-used collections archiving database. The work that I have done on this collection will aid in the curation of an exhibit celebrating Monroe County’s Bicentennial in 2020.

Another project I completed was transcribing the 1850 and 1860 slave censuses from Monroe County, Kentucky to make them accessible on TopScholar. This was a particularly significant project to me because I feel that a lot of valuable information is contained in these records. The slave census gives insight into the early history of Monroe County and the significance of enslaved people in its development. I learned a great deal from this project, and it sparked many questions that led me to look deeper into the county’s history. Not only do the records give information on slave owners, but they also give information on the age-sex distribution of slaves and the ways in which they were classified in that time period.

I also researched my hometown of Red Boiling Springs, Tennessee and wrote a historical overview that is available on TopScholar. Red Boiling Springs borders the Tennessee-Kentucky line and is known for the several types of mineral waters that flow throughout the city. The medicinal properties of the springs once attracted visitors from all over the country and created a booming resort industry in the small town. I am passionate about preserving the history of Red Boiling Springs, and I have done independent research on it for over a year now. I am grateful that I had the opportunity and support from Library Special Collections to publish information on this small but significant community.

Throughout my time as an intern with Special Collections, I have gained experiences that will be valuable in my future such as scanning, writing, and cataloging in Past Perfect. Most importantly, I have learned how to use library and archival resources for research. I also learned so much about myself and the Kentucky and Tennessee counties that have influenced my life. I am grateful for the sponsorship of Dr. Delroy Hire and the opportunities that this internship has opened up for me. Any student who is interested in the Hire Internship can contact Department Head Jonathan Jeffrey by phone at (270) 745-5265 or by email at jonathan.jeffrey@wku.edu.

Written by Hannah Hudson