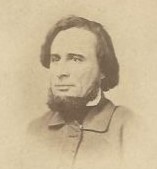

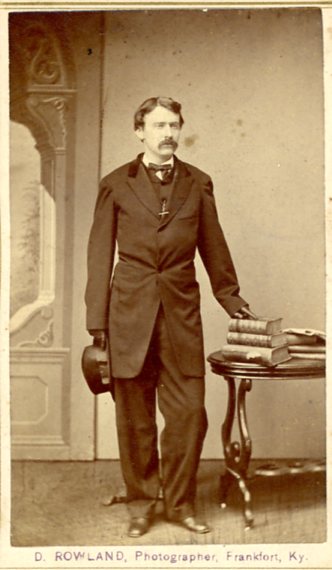

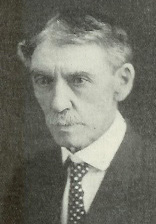

As we have seen, Edward R. Weir, Sr. (1816-1891) of Greenville, Kentucky took an active role in advocating, arming and funding the Union cause during the Civil War. His entire family, in fact, opposed secession. Weir’s wife Harriet defiantly nailed the U.S. flag to a tree when Confederate Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner toured Muhlenberg County. Weir’s daughter Anna helped raise volunteer home guards and made pocket needle-and-thread cases for soldiers’ kits. Weir’s son Edward, Jr. served as an officer in two Kentucky infantry regiments, and saw action at Shiloh, Corinth, and Saltville, Virginia.

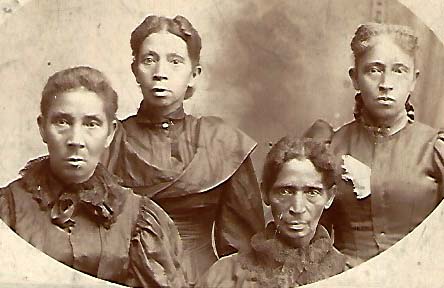

But Edward Weir Sr. was also the owner of some 100 slaves, and therein lies the tale of another family. Weir’s youngest son Miller (1859-1935) recalled the patriarch of this family, known as “Copper John.” Copper John’s daughter Amy was Miller’s nurse and maid to his mother Harriet. Amy’s four sisters also worked in the Weir mansion, the centerpiece of a 1,200-acre plantation.

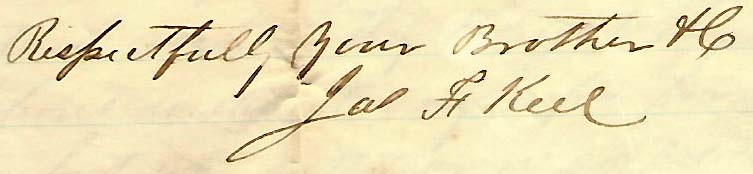

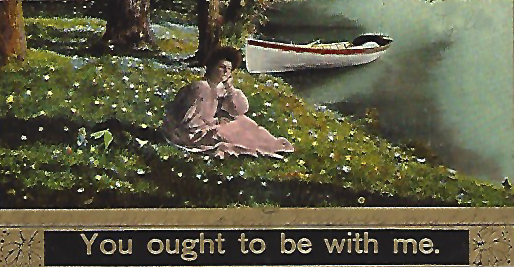

The sisters had two brothers, Silas and Jesse (or Jessey). It was the latter who, as cook, manservant and companion, made Edward, Jr.’s life considerably more bearable after he entered military service. Writing from Camp Calhoun in McLean County, Edward described his tent, a spartan but comfortable space. “I have a grand time & live like a king all alone with Jessey,” he told his family. “I sleep on one side & Jessey on the other,” with a small stove for warmth. His modest dinner table, with its tin cups and plates (and one china plate “for the Captain” as Jessey said), was evidently a source of pride and comfort for Edward. Even when he was ill and out of sorts at Corinth, Mississippi, he boasted of Jessey’s culinary skills and his ability to make biscuits just as good as those back home.

With the exception of Amy, who died in Chicago, the later lives of the children of “Copper John” are unrecorded. Edward Weir, Sr., however, praised the intelligence and resourcefulness of his former slaves; one became a missionary, another attended Oberlin College, and others became teachers. And during the upheaval of the Civil War, he gratefully remembered, they “watched over me and mine, with a devotion which I shall never forget.”

The Weir Family Collection of letters and photographs is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.