In thousands of World War II soldiers’ letters in the collections of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives section of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections, servicemen express their patriotism, love of family, apprehension, boredom, determination, and a host of other emotions. Reading of a man’s hopes for the future, however, is especially moving if we know that he didn’t make it home to realize those hopes and dreams.

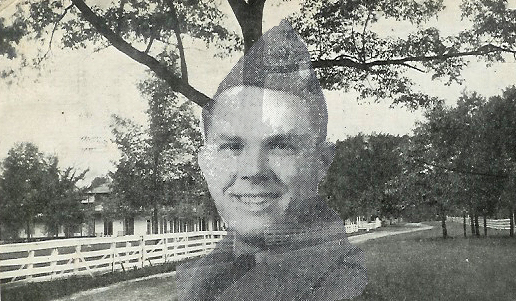

Edmonson County, Kentucky native James “J.C.” Browning left his teaching job, wife Lila and infant daughter for service with the U.S. Army at Fort Knox in August 1941. He trained in Ireland, then embarked for North Africa, where he was killed in November 1942 during the Allied invasion campaign known as Operation Torch. But J.C.’s letters to Lila rarely dwelt upon the threats he faced (he seemed more worried about what would happen to their baby if Lila died while he was overseas!) Instead, he returned time and again to one of his fondest wishes: that after the war they would purchase a home. As these excerpts from his letters show, J.C.’s dream was vivid, and no doubt sustained him until his death:

If we really save while I am in the army this year we can make a down payment on our home somewhere. . . . We would admire it and love it as we made it better and better. I’m really looking forward to that.

I would like to buy a home as quickly as we can. . . . It takes an awful long time to build up a farm home that we would be proud of. That is what I want and I will never be satisfied until we get started on it.

We want a very fertile farm close to town. It should contain about 80 or 90 acres and have the modern conveniences of town. In other words we want a town home out in the country.

Remember that we have a home to establish and it is a semi-country home. It should contain about a hundred acres of good land and a tenant house because most of our work will be done for the public.

We must select a good location, one that we would like when we are old as well as now. We should know what we are going to be doing 10, 20 or more years from now. We must think and plan things to the best of our ability.

Click here to access a finding aid for J. C. Browning’s letters to his wife Lila. For other World War II collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.