Dr. Walker Rutledge, WKU Professor of English, annually brings his English 300 class to the Kentucky Building for an introduction to manuscript collections held by Library Special Collections. Afterwards, the students select a collection to read and then write a summary related to it. The following is Cameron Fontes’ paper. He chose to write about the Mansard Hotel register from the collection (SC 1236). To see the finding aid for this collection click here.

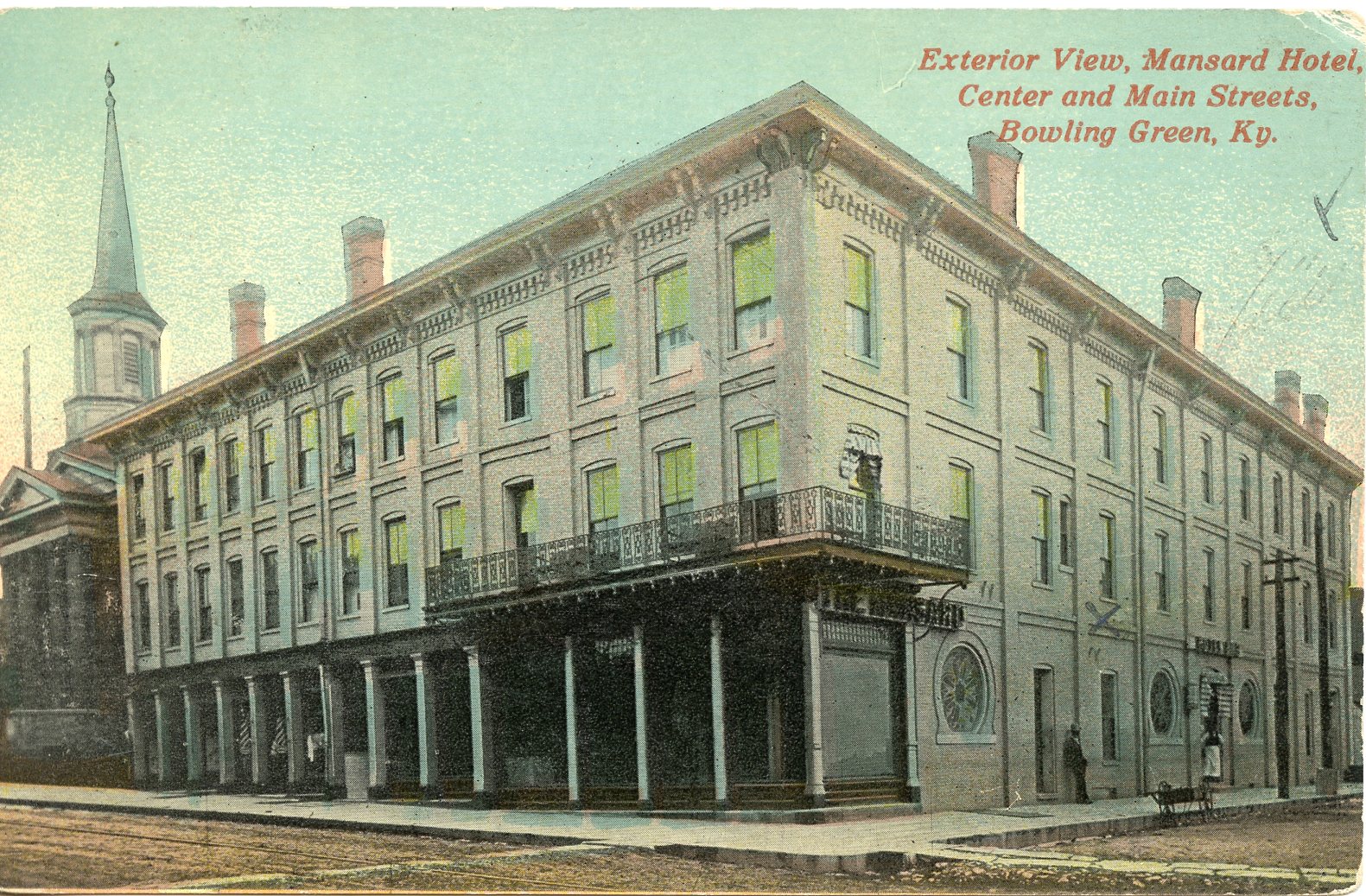

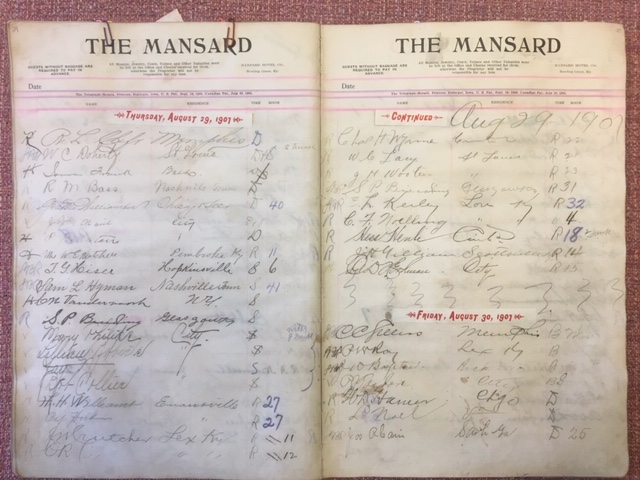

Unlike the many impersonal, chain-owned hotels of today, the Mansard Hotel in Bowling Green, KY, encapsulated all the best parts of its community. It was a locally-owned, well-kept institution where local leaders and travelers alike commingled amidst luxurious, yet affordable, furnishings and convenient eateries. When guests arrived at The Mansard, either for just a meal or for an overnight stay, they recorded the details of their visit on the tall, lined pages of the hotel register in grand, gorgeous script. Although it is now yellowed and musty with age, he Mansard Hotel register kept from 16 August 1907 to 7 October 1907, provides an intimate and detailed portrait of the bustling environment of a small-town hotel in the first decade of the twentieth century.

Located behind what was then the local opera house, the Mansard stood near the corner of Main and Center Streets in downtown Bowling Green. At check-in, one of the register columns guests were required to fill out if they were staying overnight was the “Room” column, in which they were to write their room number as well as the number of pieces of luggage they brought with them. Although the number of pieces each guest brought with them is nothing especially noteworthy, one interesting observation that can be made upon reading the record of each guest’s luggage is that for the most part, guests only used trunks rather than suitcases, which are probably the most common type of luggage in use today. On 7 September 1907, a guest who signed as “E. Jenkins” from Buffalo, New York, brought with them one trunk and stayed in room seven.

Buffalo was only one of a plethora of places from which guests at the Mansard traveled. Each guest wrote their place of origin in the register column marked “Residence,” their responses ranging from various towns within Kentucky, such as Golden Pond and Louisville, to St. Louis, Missouri, Evansville, Indiana, and many cities besides. If a guest were visiting simply to take in a meal at the hotel restaurant, they wrote “City” to indicate that they were a resident of Bowling Green. One especially fascinating entry in this column on 24 September 1907, is that of Ed H. Foster, who signed that he was from “Coffeetown,” a small town in Pennsylvania located, funnily enough, about five miles from the town of Hershey.

It is evident which guests in the register were only visiting for a meal by whether or not they write a room number in the “Room” column next to their response in the “Time” column. Obviously, if there was a room number in this column, that was the room in which the guest who signed on that line stayed. If there was no room number, however, one has only to look at the guest’s response in the “Time” column to see for which meal they made a trip to the Mansard. Each guest signed either a “B,” “D,” “S,” or “R”. Most likely, the first three letters indicated the meal at which each guest dined or the closest meal to which each guest checked in for their stay, “B” being for “Breakfast,” “D” for “Dinner,” and “S” for “Supper.” “R” would likely have stood for “Resident,” seeing as how the demographic of permanent residents of hotels was much more common in 1907 than today.

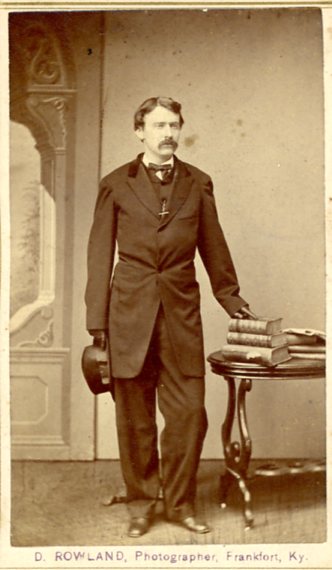

One very famous Bowling Green resident who visited the Mansard for breakfast om 2 September 1907, was none other than Henry Hardin Cherry. Western Kentucky University’s first president, Cherry signed his name in big, beautiful cursive along with the name of his beloved hometown, making sure to proudly write out “Bowling Green, KY,” instead of simply “City,” as so many others had done. That he would have been well-respected and well-known at the time is likely. Having just become the president of what was then “Western Kentucky State Normal School” the year before, he would have already been considered a bastion of higher education in the community.

Other notable guests at the Mansard during this time included C.W. McElroy, a state representative for Bowling Green, on 21 August 1907, for supper, along with a couple of other individuals with prominent Bowling Green names including R.B. Potter from Woodburn, Kentucky, on 9 September 1907, and N.J.M McCormick from Indianapolis, Indiana, on 10 September 1907, who may have both been in town visiting family.

Sadly, the Mansard Hotel burned down on 5 July 1969. To stay in a hotel as charming as the Mansard may seem impossible today, but by perusing its old register one can start to gain a sense of its local charm and grandeur. cked