Heartbreaking memories of the 1918 influenza pandemic. The FBI dossiers on a husband-and-wife team of socialist labor activists. Gracious letters from Gone With the Wind star Olivia de Havilland. The gritty details of a guest’s sudden collapse and death during a television talk show. Accounts from survivors of one of America’s worst wartime naval disasters.

Where can you find all of these within easy reach of one another? In the papers of Dr. Carlton L. Jackson, a prolific author and historian who donated a large portion of his research and manuscripts to WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Processing of the 4,336 items in this collection was completed in October, which happens to be American Archives Month. A finding aid is available here.

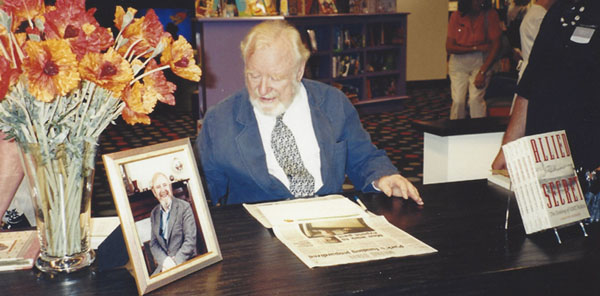

Carlton Jackson’s career as a history professor at WKU began in 1961 and continued until his death in 2014. A high-school dropout, the Alabama native resumed his studies during service in the Air Force, then taught school and worked as a newspaperman before arriving at WKU. The author of more than 20 books, he also held several Fulbright awards and visiting teaching posts, and in 1996 was appointed WKU’s first Distinguished University Professor.

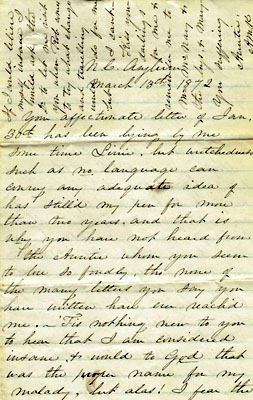

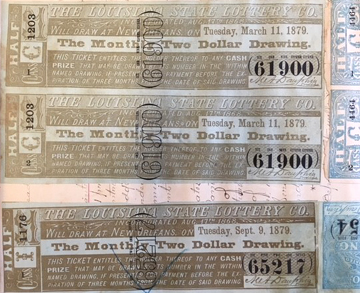

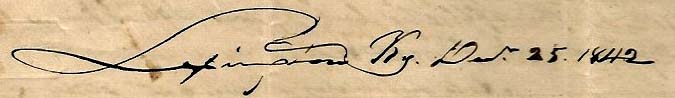

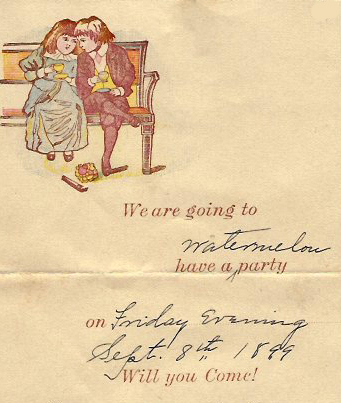

Jackson’s books included Hattie: The Life of Hattie McDaniel, a biography of the Oscar-winning actress who immortalized the role of “Mammy” in Gone With the Wind; Allied Secret: The Sinking of HMT Rohna, an account of the 1943 guided missile attack on this troopship that killed more than 1,000 American servicemen; J. I. Rodale: Apostle of Nonconformity, a look at the self-described “father of the organic movement” in the United States, whose life ended suddenly while a guest on the Dick Cavett Show; and Child of the Sit-Downs: The Revolutionary Life of Genora Dollinger, a biography of this workers’ rights champion whose career began in earnest during the great 1936-1937 “sit-down” strike at the General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan. Other books of Jackson’s have told the story of the iconic World War II song Lili Marlene; related a social history of the Greyhound Bus Company; assessed the career of movie director Martin Ritt; recalled the heroism of Joseph Gavi, a Louisville restaurateur who was once a partisan fighter in the Jewish ghetto of Minsk; and novelized the life of George Al Edwards, a Green County, Kentucky outlaw. For a 1976 book on the 1918 influenza pandemic, Jackson placed ads in newspapers across the country seeking eyewitness accounts, and received more than 400 replies documenting the flu’s deadly march through 42 states and 9 foreign countries. The book was never completed, but this unique collection of letters has been preserved.

“Dr. Jackson’s research and writing testified not just to his energy but to his eclectic interests and inveterate curiosity,” says WKU Special Collections department head Jonathan Jeffrey. Searching for sources in both public archives and private collections, Jackson corresponded with anyone who might provide a lead. As a former journalist, he never hesitated to seek a telephone or personal interview, making many friends along the way. As the collection reveals, his efforts generated wins and losses, both big and small. While researching a biography of Western novelist Zane Grey, Jackson wondered if Grey’s tales of shark fishing had influenced Peter Benchley’s blockbuster novel Jaws, but Benchley politely replied in the negative. A greater disappointment occurred when, after his initial contacts proved promising, the Greyhound Bus Company withdrew its cooperation for Jackson’s history. He scored a coup, however, when he located and corresponded (in German) with the pilot of the plane that had attacked the Rohna.

“I’m basically lazy,” Jackson once insisted in a profile published in WKU’s On Campus. But it never showed. After he got an idea for a book he would begin work, reading, traveling, knocking on doors and, like a good ex-journalist, digging. The result, in addition to his publications, was a trove of research, now available to anyone else who wants to keep digging.

The Department of Library Special Collections is located in the Kentucky Building on WKU’s campus. Hours are Monday-Friday, 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Search our online catalogs at TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.