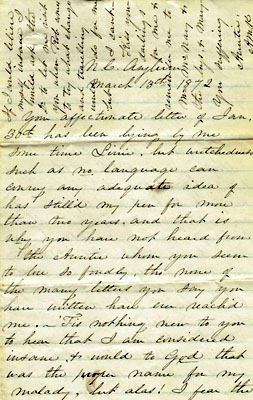

“If we have to die had we not better die together?” That was the question members of the Parker family of Hickman, Kentucky asked each other in spring 1861. Lucy Robbins, the recently widowed daughter of Josiah and Lucy Parker, was staying with her brother-in-law near Memphis, Tennessee, but her parents were desperate to have her and their young grandson come home. Letters to Lucy, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections, provide a vivid picture of lives upended by the Civil War.

At the outbreak of war, the Mississippi River town of Hickman was still recovering from a fire so destructive that it was seen from Cairo, Illinois, some 40 miles away. But now Cairo itself posed the threat, with rumors of soldiers massing there to mount an invasion from the North. Lucy’s father had heard of still more troops gathering at New Madrid, Missouri. Caught between these two armies, Josiah Parker feared that Kentucky “will again become the dark and bloody ground.” Lucy’s mother wrote of the anguish of Hickman’s women: watching in fear as their husbands and sons chose sides and enlisted, many had packed up their households and were ready to “go to woods” if the enemy should appear. “O what shall we do pray to god for our country,” she cried.

Each successive letter from home told Lucy of the war’s shadow over her family. Her father, a local judge, lost his livelihood when the legislature temporarily suspended the courts. Her brother Matthew joined the Union Army (and would die in service), even as some of his neighbors cast their lot with the Confederates. Nevertheless, some of the town’s young women, including Lucy’s sister Lockey, refused to take a furlough from the marriage market and continued to preen in new dresses and bonnets whenever they could get them from places like St. Louis. Lucy herself returned to Hickman in 1863, where she contemplated remarrying. When she asked her dead husband’s brother for advice, he was clear: NO secessionists. Having been financially generous with Lucy as long as she was widowed, Curtis Robbins declared that his continued support would be jeopardized if she allowed a Rebel to raise his brother’s child.

Lucy, however, didn’t listen. Not only was he a Rebel, but her new husband, George J. Ligon, served under Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest and was severely wounded at Harrisburg, Mississippi. If this condemned Lucy in the eyes of her brother-in-law, another young man who had worked for him and who remained Lucy’s friend was more forgiving. Writing to her in 1864 during his Union Army service, he expressed regret that Lucy’s husband had been “crippled”; “I guess he is in the Southern army”—but, he shrugged, “you know it is all the same to me.”

A finding aid for family letters to Lucy (Parker) Ligon can be accessed here. For more Civil War collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.