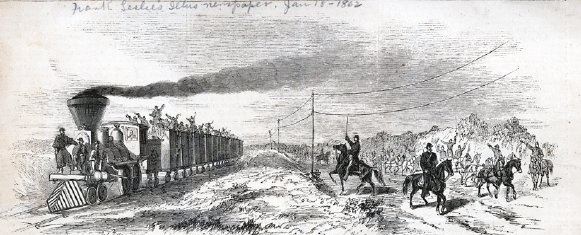

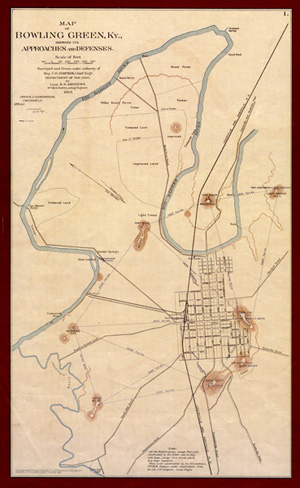

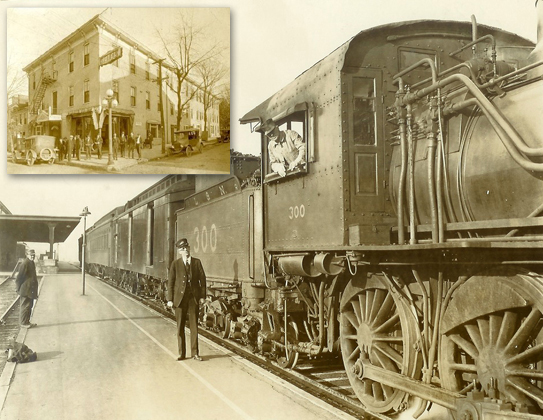

Minute obstacles can cause huge delays when moving armies. If anyone doubts this, they need only see how a small accident or distraction can stymy traffic on a major interstate. During wars, strategic transportation routes are often heavily reconnitored or destroyed in order to impede an army’s progress. In Kentucky roads and railroads were of major importance for moving troops and supplies during the Civil War, particularly in the interior. Steamboats were more significant on the Commonwealth’s perimeters.

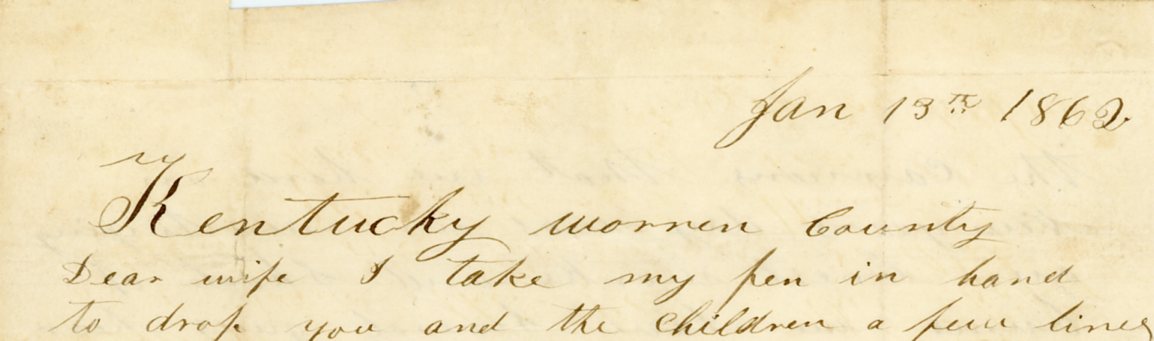

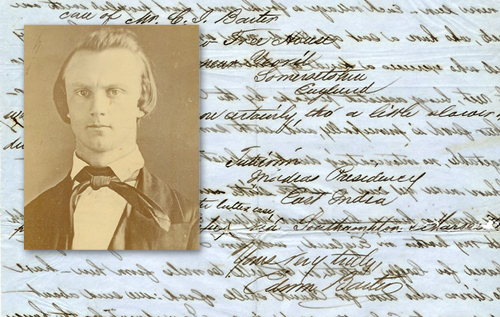

In a letter recently donated to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives unit of the Department of Library Special Collections, Confederate J.J. Williams writes to his wife Emeline about how the southern army had played menace with the Louisville and Nashville railroad, which had only recently been completed through Bowling Green. To disable the railroad, Williams wrote, “our men had torn up the rail road some 5 or 6 miles and Blowed up the tunnel and burnt the ties[,] beat the rails to pieces with a Sledg[e].” They wreaked further havoc by blockading the Louisville and Nashville road “by cutting the trees a cross it for a bout 3 miles and Some other Place they have plowed up the road so they can not haul a thing a long it.” To see the finding aid for this small collection and a typescript of the letter, click here.

To search finding aids for hundreds of other Civil War letters in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives unit, click here.