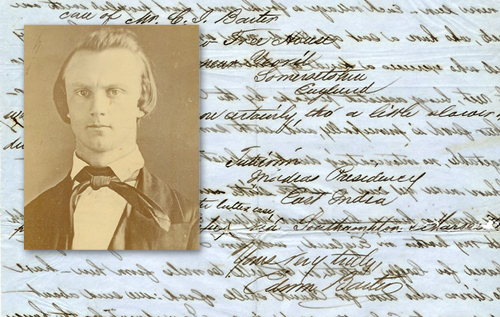

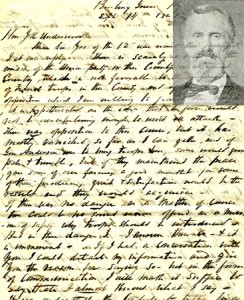

The acquaintance of Edwin Barter and Colonel Benjamin Covington Grider of Bowling Green dated back to the first year of the Civil War, during Grider’s command of the Union’s 9th Kentucky Infantry. When Grider next heard from him, Barter had left his home in England to pursue the cotton and coffee trade in India.

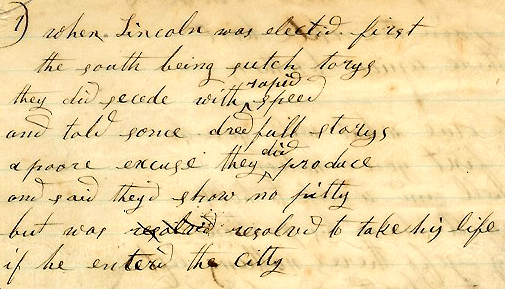

In an August, 1865 letter from Madras Province, Barter observed that America had finally turned a page. “The war for Southern rights is well nigh over, and ‘subjugation’ ‘Coercion’ and ‘precipitation’ are words buried,” he declared. Now it was time to “count the cost” of “3/4 century’s folly and vice.” Barter had heard that a local judge was out to get Robert E. Lee, but couldn’t imagine Americans being vindictive toward the Confederate general.

Once in India, however, Barter struck a more mercenary tone toward its brown-skinned inhabitants. Regarding them with an air of superiority common to many in the West, he likened them to primitives who “draw water from the well and cook their simple food after the same style as their ancestors who lived before Britain was known to the Romans.” He scorned the natives at length as mendacious, lacking in “go-a-headativeness,” and seemingly immune to attempts to introduce them to the benefits of Christianity and European civilization. India, he remarked, has “180 million of inhabitants who are governed by 3 or 4 hundred thousand Britains [sic] who exile themselves for a certain number of years, never, or very seldom indeed, permanently settling in the Country, but ever looking forward to the day when they will have pocketed enough to turn their faces towards home.” Barter described his own prospects as good, but agreed that he was not “at home.” “How long residence?” he asked tersely–wondering, perhaps, about the political costs awaiting Britain in three-quarters of a century.

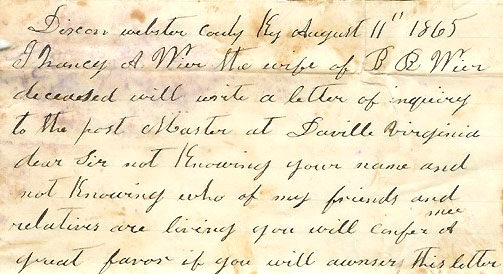

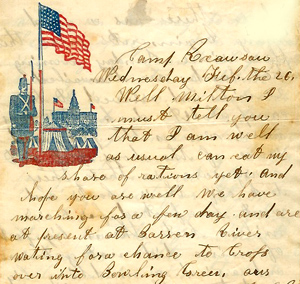

Edwin Barter’s letter to Benjamin Grider is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more of our collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.