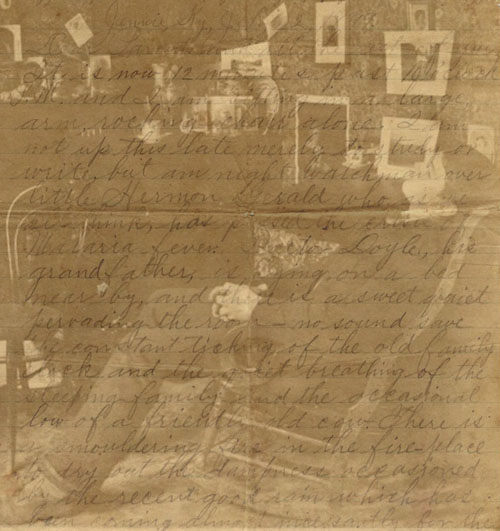

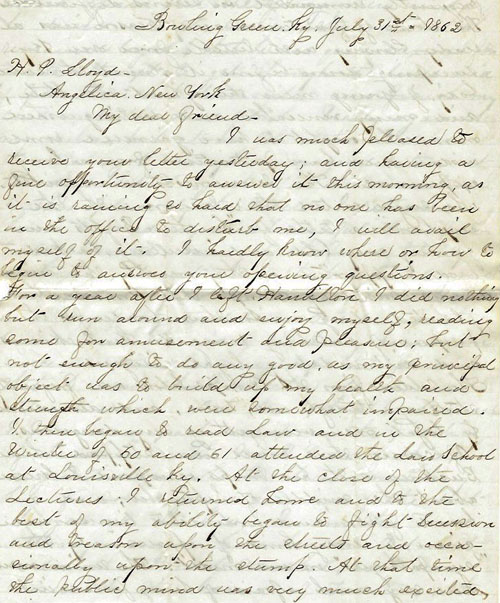

His letter written 158 years ago today showed the 22-year-old negotiating life in fits and starts.

After graduating from New York’s Hamilton College in 1859, Hector Voltaire Loving had returned to his home town of Bowling Green, Kentucky. For the next year, he confessed in a letter to a classmate, “I did nothing but run around and enjoy myself,” hoping that such leisure would allow him to “build up my health and strength.”

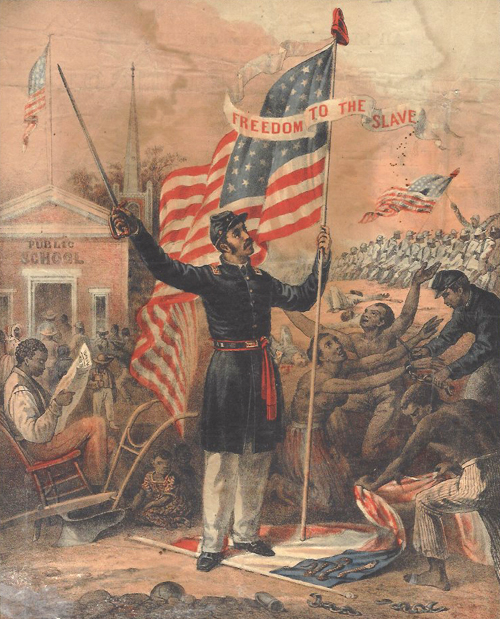

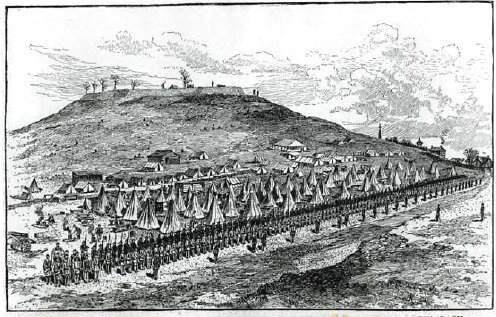

Finally, Hector roused himself to begin law studies in Louisville, but at the close of the 1861 school year returned again to Bowling Green to find the city in turmoil. Civil war was bearing down on Kentucky, “the public mind was very much excited,” and “discussions were growing very violent.” The young man was repelled by the “storm of fanaticism and treason” and by “the secessionists in our midst, who sugar coated their treason with the euphonious title of ‘Southern Rights.’” Despite growing intimidation by rebel troops who “strolled through our town” from military encampments across the Tennessee line, he had resolved to speak out against the “Secesh.”

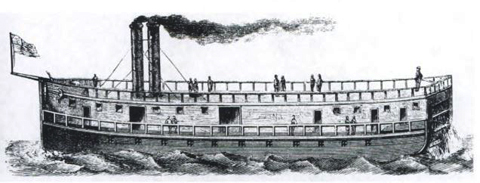

After the Confederates occupied Bowling Green in September 1861, however, Southern sympathizers gained “unlimited license.” Hector’s father, worried that his son would be forced into the ranks of the rebel army, had urged him to make his way back to Louisville and finish his law degree. Hector succeeded, only to come home again early in 1862 just after “the evacuation of this place by the Rebels” had ended the occupation. He was dismayed at the state of “my once beautiful town.” Bowling Green was left “partially burned, many of the fences totally destroyed, almost all of the beautiful groves cut down, and the sidewalks and streets in a very filthy condition.”

Fortunately, wrote Hector, a clean-up effort and some cleansing rains had now restored the city to “much of its former attractiveness.” He had entered into partnership with an established lawyer and even gained appointment as the town’s attorney. “I am in a position to do very well and enjoy myself when the war is over,” he declared, but was still conscious that “owing to the uncertain condition of affairs and the feverish excitement constantly prevailing people have not yet gained full confidence.” Indeed, there was much to be resolved about the comeback. The Confederates had been driven no farther away than Tennessee. Hector’s own father, a prominent lawyer, legislator and judge, maintained enslaved labor on his farm. And another of Hector’s Hamilton College classmates was back home in Bowling Green, too, planning to go North to law school despite being a “very violent ‘Secesh.’”

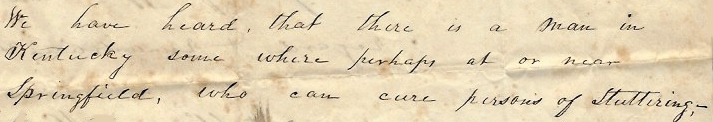

A finding aid and typescript of Hector V. Loving’s letter can be accessed by clicking here. For more collections in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.