Learn about some of the unique primary source materials in WKU’s Special Collections Library. To browse further, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

Freedom! Let the World Rejoice!! Hence for the first time since the writer was born – nearly 59 years, can we hire men, & pay them for their service instead of working them & paying their so called Masters & Mistresses the money earned by the sweat of their brow.

– Harvey L. Eades, an elder in the Shaker colony at South Union, Kentucky, upon learning in February 1866 of the ratification in December 1865 of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

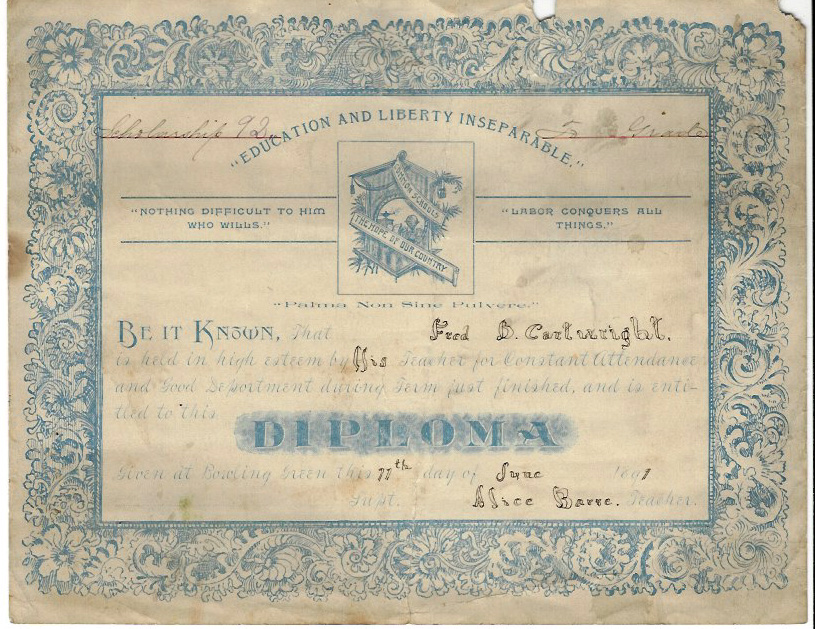

I had rather have the wisdom than the bliss, as dear old mother Eve chose before me!

– Bowling Green, Kentucky schoolteacher Sallie McElroy, reflecting in 1857 on the saying “Where ignorance is bliss, ‘tis folly to be wise.” Read more. . .

Every disaster which takes a toll of human life brings forth its heroes.

– Thomas E. Jenkins, vice president of the West Kentucky Coal Company, in a 1927 letter of thanks to miner Earl Hamby for his help in recovery efforts after an explosion killed 15 of his coworkers. Read more. . .

I am in a world of trouble. Sophia.

– Captain Richard Vance, upon the death in 1889 of Sophia, his African-American mistress, homemaker and companion through 22 years of military postings through the South and West. Read more. . .

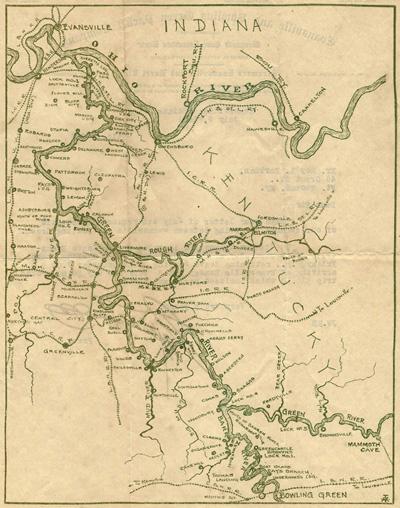

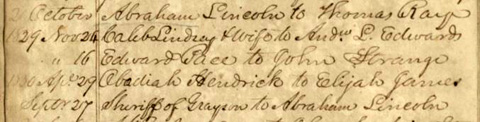

There are no national parks east of the Mississippi River and there is no place east of the Mississippi River so well known as Mammoth Cave. . . . Mammoth Cave has been exhibited to the public for more than a hundred years. It is mentioned in the records of Warren County as far back as 1797.

– Marvel Mills Logan, president of the Mammoth Cave National Park Association, urging the Secretary of the Interior in 1925 to begin the process of making Mammoth Cave a national park. Bowling Green banker Max Nahm took a leading role in the project. Read more. . .

Just imagine yourself with sixty brats, all under thirteen . . . . a half dozen in my class would be having a fist and scull fight and the whole of them had even forgotten what their lesson was about.

– Henderson County, Kentucky schoolteacher Virginia “Jennie” Amos, to her former classmate May Carpenter, lamenting her duties in 1889. Read more. . .

We lay flat upon the ground for a long time, the missiles of the enemy falling thick & fast among us, wounding many and sending some of our comrades to eternity, among these were Charles Jameson, shot in the shoulder and probably through the heart, Charles Beard shot in the head, and Henry Hildreth, shot in the cheek.

– Michigan volunteer Jason Wiltse, describing the Battle of Campbell’s Station near Knoxville, Tennessee, November 16, 1862. Read more. . .

Some assistance to build a house is greatly needed 2 axes 2 hoes and 1 spade was all the children get to farm with, no cutlass no grass scythe no mattock. I did not even get a water Bucket.

– Emancipated slave Rachel Eddington, writing in 1857 to her former mistress from Liberia, where she endured poverty, abandonment by her husband, and the deaths of two children. Read more. . .

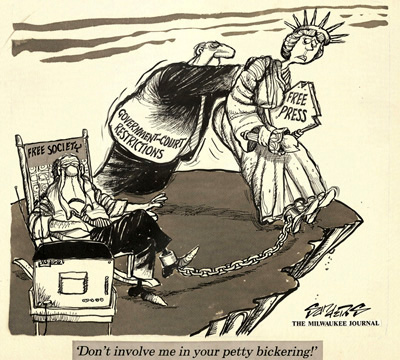

Don’t involve me in your petty bickering!

– Bill “Whitey” Sanders, WKU alumnus and longtime editorial cartoonist for the Milwaukee Journal, where his liberal views and devotion to free speech often enraged politicians and the public.

The Sec[retary] read a letter from headquarters with reference to the riot at Tulsa [Oklahoma]. A motion prevailed that the churches be asked to take a special offering for the stricken & suffering of Tulsa.

– Minutes of a meeting of the Bowling Green, Kentucky branch of the NAACP, June 12, 1921, on hearing of the white supremacist massacre that killed hundreds and destroyed 35 square blocks of African-American homes and businesses in the Tulsa community known as “Black Wall Street.” Read more. . .

That the inhabitants were horror stricken is not to be wondered at, but that they were anything but lunatics afterwards is.

– Betsy Taliaferro, speculating in on the mental health of the citizens of New Madrid, Missouri, twenty-five years after earthquakes in 1811-1812 levelled the town and sent aftershocks through southcentral Kentucky. Read more. . .

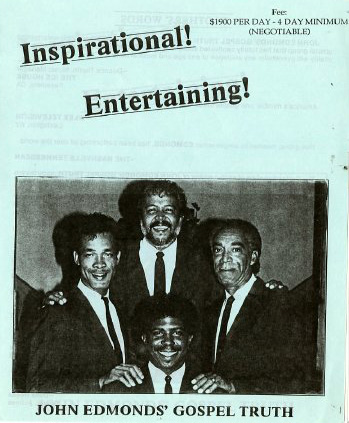

The Black Gospel Music World has always consisted of, been inclusive of, and been a haven for gay men and lesbians. If the truth were to be told, many of your biggest names in Black Gospel through the years were gay or bisexual.

– Bowling Green native John Buell Edmonds, promoting Called, Justified, Glorified and Gay, a fictionalized account of his life as a gay African-American gospel music performer.

I was a patient in a North India Medical College Hospital. I was recovering from post-polio muscle transplants. There in that Hospital I heard along with the rest of the world the announcement that Dr. Jonas Salk and his associates had reported a polio vaccine 60-90% safe. Tears of joy came into my eyes.

- Christian missionary Marietta Mansfield, on learning in 1955 of the successful development of a polio vaccine. Read more. . .

There is every appearance of success in our taking Lord Corn Wallis. Our Army is very strong. I suppose we have twenty thousand men in the field. They are in high spirits wish to be in action.

– Nathaniel Lucas to his sweetheart Sarah Rivers, September 15, 1781, just before the siege of Yorktown, Virginia and the surrender of Lord Cornwallis that foretold victory in the American Revolution.

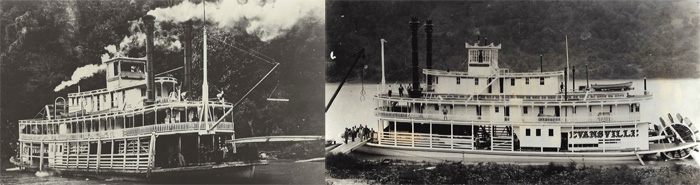

I’ve always felt our ship might have had the same fate it we hadn’t had a good captain and a slow boat.

– Jennie Scott Green, after returning from Europe to her Grayson County, Kentucky home in 1912 on the President Lincoln, a ship sailing just ahead of the doomed Titanic. Read more. . .